Last updated:

‘"Notoriously abandoned characters": searching for the women in the Western Gaol 1854–58’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 22, 2025. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Sarah Mirams.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Female prisoners in Melbourne were incarcerated in the Western Gaol on Collins Street from 1854. Drawing upon archival and newspaper sources, this article explores the history of the Western Gaol from 1854 to 1858 and describes its repurposing and renovation as a female gaol in gold rush–era Melbourne. Archival sources provide insights into the administration of the gaol and its built history and provide glimpses of the women and their lives in the gaol. My research suggests that the Western Gaol played a contradictory role in the lives of women, both as a place of punishment and, at times, of refuge for the poor, the sick, the homeless and children.

Introduction

‘Miserably inadequate, badly situated and unsuitable for a goal of any kind … especially for females’, was how the Legislative Council Select Committee into Penal Discipline described the Western Gaol in September 1857.[1] The report decried how women on remand mixed with ‘notoriously abandoned characters serving long sentences’ and recommended the closure of the Western Gaol.[2]

The Western Gaol, located on Collins Street in the block between King and Spencer streets, was one of a number of gaols, stockades and prison hulks commissioned to hold prisoners across Melbourne when crime rates rose dramatically following the discovery of gold in 1851. The rapid increase of Victoria’s population, fuelled by migration from other colonies and overseas, saw the crime rate rise exponentially.[3] In 1851, there were 28 of ‘the fair sex’ gaoled in Melbourne.[4] This increased to 308 in 1852 and 382 by 1854. The numbers of women incarcerated in 1855 had blown out to 1,162.[5] The Western Gaol held the majority of female prisoners in Melbourne, both long and short term, from 1854 to 1858. A handful who required close security were imprisoned in the Melbourne Gaol in Russell Street.

The Western Gaol was a constant in the life of women who fronted up to the Melbourne courts from 1854 until 1865, making it a place of some significance in Melbourne’s gold-era story. This article describes the built history of the gaol, its management and the conditions in which the women, and often their children, were held. I argue that while imprisonment in an overcrowded and dank building punished women by denying them their freedom and comfort, paradoxically the gaol provided a place of safety for vulnerable women and children in times of crisis and need.

This was a period of social and economic upheaval in the new colony. The discovery of gold saw Melbourne transformed from a town servicing the pastoral industry to what historian Graeme Davison dubbed an ‘instant city’ by 1854.[6] With the lure of gold quadrupling the colony’s population between 1851 and 1861—from 77,000 to 540,000—Melbourne’s streets were overcrowded, housing and shelter were in short supply, and the authorities struggled to maintain public health and public order. There were 193 men to every 100 women in the colony and most were aged between 20 and 40. It was a society on the move. Men flocked to the goldfields, many leaving wives and children behind in Melbourne. The plight of deserted and widowed women became a serious social issue that consumed colonial authorities.[7] Some immigrant families were forced to live in tent cities where disease spread quickly. Alcohol was particularly toxic in the colony, the brandy often laced with narcotics and other additives that could send people mad. Janet McCalman describes it as the equivalent of modern-day methamphetamines—it fuelled violence and crime.[8] The boom years of 1852 and 1853 gave way in 1854 to an economic slump, high unemployment and low wages.[9]

The end point of my research is 1858 when female prisoners sentenced to more than 14 days were increasingly sent from the Western Gaol to the prison hulks Sacremento and Success off Willamstown in Hobsons Bay to serve out their sentences. From 1858 until its closure in 1865, the Western Gaol held women on remand, elderly male vagrants formally held in the Eastern Gaol and the mentally ill awaiting transfer to Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum. The Western Gaol was demolished in 1865, the land sold and used as a timber yard. In the 1880s, warehouses were built on the former gaol site. In the 1960s, the warehouses were replaced by an office building at 582–606 Collins Street. This was demolished in 2023. The Western Gaol was located beneath part of this office block. This address was registered on the State Heritage Inventory during demolition as a place of potential archaeological significance under the Heritage Act 2017.[10] My research into the Western Gaol began as the historian commissioned to prepare the archaeological assessment for 582–606 Collins Street in 2023.

Female prisoners

This article draws upon existing research carried out into women and criminality in gold rush–era Melbourne. Janet MacCalman’s Vandemonians paints a vivid picture of the criminal underclass in gold rush Melbourne and the opportunities the city’s new riches and social disruption offered to the old hands from Van Diemen’s Land.[11] Prostitutes were the symbol of female criminality for respectable Melbournians, and their work and lives are explored by Raelene Francis, Sarah Hayes and Barbara Minchinton.[12] The significance of the vagrancy acts across Australasia, including Victoria, on the policing of women is interrogated by Catherine Coleborne.[13]

The Western Gaol and the experiences of women living within its walls have never been studied. The history of female imprisonment in nineteenth-century Australia was largely neglected until the 1990s, aside from that of convict women.[14] Recent historical research into female prisoners in Victoria has drawn upon the rich resources found in the Central Registers of Female Prisoners held at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV). Researchers have undertaken longitudinal studies investigating the criminal careers of 6,042 female offenders held at the Melbourne Gaol from 1860 to 1920 to identify patterns in the gendered nature of their offending; the influence of age, location and familial relations on criminality; and relationships between offenders.[15] This research has proved invaluable in understanding female criminality in the nineteenth century.

The focus of this article is women’s experiences within the walls of the Western Gaol. Current installations and exhibitions telling the stories of female prisoners at the Melbourne Gaol, now the Old Melbourne Gaol, a prison tourism destination, look outwards, focusing on the city and the political, social and economic conditions that led to their incarceration.[16] This article takes a different approach, taking its lead from Lucia Zedner who, in her history of English women in custody in Victorian England, argues that prison history should be written from within, with the significant actors being the inmates, warders, medical staff and administrators within the gaol walls.[17] This approach provides an understanding of the gaol routine and conditions, and allows us to consider to what extent the gaol fulfilled its role of punishing and reforming. The experience of the prisoner inside, rather than the criminal outside, takes centre stage.

The archive

The female inmates left no memoirs, letters or books to interrogate; however, snapshots of their gaol experiences can be found in Victorian government archives. These archives form the basis of this research. My approach is informed by the work of Janet McCalman and Clare Anderson who demonstrate how the seemingly marginalised and invisible can be found, almost accidently, where their lives intersect with government authority.[18]

Researching the Western Goal posed archival challenges. PROV holds few records of the Western Gaol. Its single record, a register of female prisoners received and discharged at the Western Gaol between 1853 and 1858, is presently undergoing conservation.[19] The Central Register of Female Prisoners Volume 1 (1855–61) provides biographical details for the cohort of prisoners transferred from the Western Gaol to the prison hulks Sacramento and Success in Hobsons Bay off Williamstown from December 1857. These are valuable sources, as they record previous sentences served in the Western Gaol. The women’s ages, aliases, former occupations, departure ports and dates of arrival in the colony, as well as their behaviour in custody, are also recorded.[20] The 1855–61 register favours the ‘old hands’ who were multiple offenders, or those who committed felonies. It does not capture information on women held on remand, or those imprisoned for misdemeanours. Such women formed the majority of inmates in gaols and are those least studied by historians.[21]

Some of the most useful insights into the management of the Western Gaol were found in letters and the reports of visiting justices held in the Inspector of Penal Establishments and the Sherriff: Prisons files, located in VPRS 1189 Inward Registered Correspondence of the Colonial Secretary.[22] Claud Farie, a politician and pastoralist, was appointed sheriff in 1852.[23] The Sheriff’s Office had responsibility for the Melbourne Gaol, Western Gaol, Eastern Hill Gaol and the regional gaols. Dr Richard Youl was appointed a visiting justice in November 1854.[24] He inspected the gaols weekly and wrote reports monthly.

In 1857, the Legislative Select Committee into Penal Discipline was established in response to allegations made by a Citizens Committee against John Price, the inspector general of penal establishments. Price was accused of overseeing a system that was cruel and harsh. (Price was murdered by prisoners before the select committee finished its deliberations.) The entire gaol and penal system was reviewed and recommendations made. Both Youl and Farie gave evidence describing conditions in the Western Gaol and their views on the female prisoners. Inquests were held into deaths in prison and the deposition files held at PROV provide glimpses into life and death in the gaol.[25] Government reports published in newspapers and court and crime reports were also valuable sources of research.

The gaol, 1840

Figure 1, a sketch by Melbourne’s surveyor Robert Hoddle, shows a view of the gaol in 1840 from the corner of Spencer and Collins streets near where Captain Lonsdale first set up camp in 1838, beginning the official British occupation of Kulin lands. The gaol was built on the Government Block, section 16, bound by King, Collins, Spencer and Bourke streets. Here, convict workshops, police and military quarters and immigration barracks were built over the next 15 years.[26] The red brick building, convict built with high windows is marked with a G for gaol.[27] Built to a watch house design, it was to be a temporary gaol until a more substantial prison could be built.[28] The goal was extended in 1842 to include a cell for the insane, an enclosed yard, solitary cells and an ineffectual treadmill, used for punishment of hard labour, installed in a mill room.[29]

Figure 1: Robert Hoddle, Melbourne – Port Phillip – 1840 from Surveyor-General’s Yard, State Library Victoria, <https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9916544173607636>.

By 1843, plans for a new gaol in Russell Street were in motion (Figure 2). The colonial secretary saw no need for two gaols in Melbourne and the Old Gaol, as it was then known, was handed over to the 99th Foot Regiment in 1846.[30] Fieldpieces and 12Ib howitzers were placed outside the gaol, their muzzles directed towards the Yarra to repel invaders.[31]

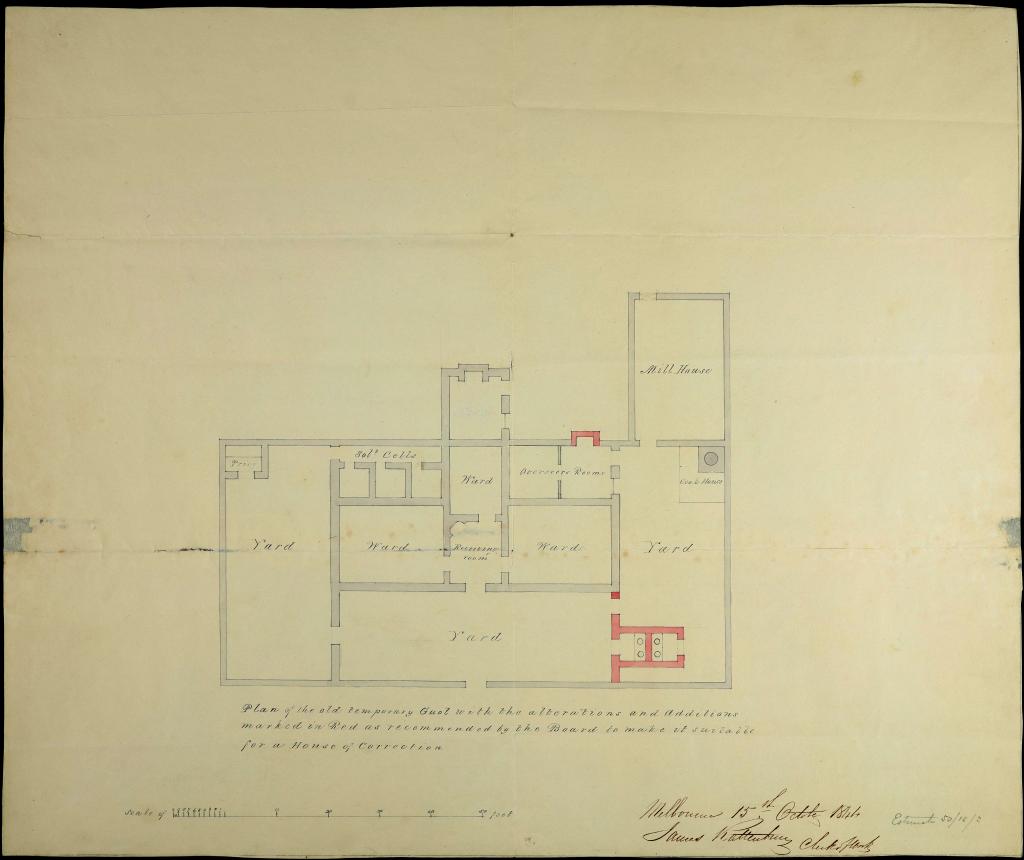

Figure 2: This plan shows the layout of the gaol before it was transferred to the military. The red lines are proposed additions that did not eventuate. PROV, VPRS 19/P0, 44/1886A Plan of Old Gaol with Proposed Additions.

House of correction

A proclamation in the Victorian Government Gazette in May 1852 announced that the building known as the Western Gaol was now a house of correction. The house of correction model originated in sixteenth-century London as gaols for vagrants or those who committed minor offences. It was believed that a regime of solitary confinement, hard labour and education in a house of correction would reform and rehabilitate inmates.[32] Similar ideas were adopted by British prison reformers in the nineteenth century. Existing prisons were dirty, overcrowded, unhealthy and often violent places that encouraged criminality though association. By contrast, it was believed that humane treatment, the separation of offenders into classes, employment, solitary confinement and religious instruction could reform offenders.[33]

William Westgarth, the chair of the committee appointed to enquire into prison discipline in Victoria, articulated these ideas in 1852, writing that prisons should be ‘not only a place of safe custody and a place of punishment, but … a place also of reformation’.[34] The discovery of gold produced an urgent need to expand Victoria’s prison system, especially after the arrival of ex-convicts from Van Diemen’s Land resulted in ‘the disorder of society and the increase in crime’.[35] The Melbourne Gaol and the minor Western and Eastern gaols were too crowded for ‘physical and moral health of the inmates’ and there was no capacity for ‘discipline and employment’.[36] Wentworth recommended urgent alterations and improvements to the Western Gaol. In 1852, he reported that it held seamen, while women were held at the Melbourne and Eastern gaols. Figure 3, a drawing of the City of Melbourne in 1854, shows the walled Western Gaol adjoining the soldiers camp on the government block.

Figure 3: In this detail of a drawing of early Melbourne, we can see the buildings in the block bounded by Collins, King, Bourke and Spencer streets (click on the link below to see the full drawing). The Melbourne Gaol is marked by the number 12. This indicates a slightly different location to the location in the Bibbs map (see Figure 4), presumably the result of artistic license. N. Whittock, ‘The City of Melbourne, Australia’, drawn from official surveys and from sketches taken in 1854 by G. Teale, State Library Victoria, <https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9917291243607636>.

The Western (or Female) Gaol—the setting

Renovation of the Western Gaol, which would become known as the Female Gaol, began in 1852. New gaoler’s quarters at a cost of £740 were built, and, in 1853, turnkey quarters for £1,200.[37] The main brick building needed to be extended and repaired, and tenders for building materials and trades for the Western Gaol were advertised in newspapers in 1854 and 1855.[38] Figure 3 shows the Western Gaol in 1854 before extensions and renovations commenced.

Figure 4: This detail from the 1856 Bibbs map shows that the Western Gaol had been extended with an additional brick building along the northern wall, one wooden building outside the perimeter of the gaol (possibly the gaoler’s quarters) and a wooden building, possibly wards, west of the original brick gaol. Three enclosed yards are shown. PROV, VPRS 8168/P3, MELBRL12; MELBOURNE.

The Bibbs map shows the site in 1856 (Figure 4): the original red brick building with the frontage on Collins Street, and the additional brown wooden and red brick buildings with three enclosed yards.[39] No architectural plans have been located showing the layout in more detail. There were six whitewashed association wards, each housing 20 prisoners, and a hospital ward. Stone cells in the 1840 gaol were used for solitary confinement and holding violent ‘lunatics’.[40] Most likely, the kitchen, laundry, privies and washrooms were external buildings. The gaol and enclosed yards measured 1,180 square metres (almost half an acre). The seven barracks of the Immigration Depot lay behind the gaol. The gaol began to take female prisoners in November 1854.

According to Dr Youl, renovations at the gaol were completed by April 1856, but there were still problems with the buildings and yard.[41] The gaol often flooded after heavy winter rains. Claud Farie asked the Public Works Department to repair the water tanks in June 1856, and the following month the gaol’s floor was raised.[42] However, the drainage problem was not resolved. In July 1857, the yards flooded once again, turning to mud, and the women and children were kept in their dormitories during the day. ‘It was impossible’, Youl wrote, ‘to confine this number of prisoners until the yards were fixed’.[43] His July 1857 report acknowledged that some improvements had been made, and that the yard had been raised and drainage improved.[44] A day room—an open walled structure where the women could shelter in the yard from the sun and the rain—was built in July 1857. It was also used as a dining area.

Despite these improvements, the gaol was still ‘a miserable place’ according to Youl.[45] It was not only the prisoners who suffered in the damp conditions. When the gaoler William Abbot, who lived in the gaoler’s quarters with his wife and three children, died in June 1857, Dr McCrae, the colony’s chief medical officer, attributed his death to ‘the damp and unhealthy nature of the whole premises of the gaol’.[46]

The offences

Most women imprisoned in Victoria during the gold rush were convicted under the Vagrancy Act 1852.[47] The Vagrancy Act was seen as a means of preserving and imposing order on a society suffering from the excitement of gold fever.[48] The Act criminalised hundreds of behaviours. You could be arrested and gaoled for being homeless and without means of support, being drunk more than three times in 12 months, illegal betting, displaying pornographic drawings, singing obscene songs or consorting with known thieves.[49] The Victoria Police Criminal Statistics for the second half of 1858 show that, of the 1,588 offences committed by females in the colony over the first six months, 782 of them, almost half, were for drunkenness or being drunk and disorderly.[50]

The terms ‘drunk and disorderly’, ‘indecent conduct’ and ‘vagrancy’ could cover a myriad of behaviours. When 48-year-old widow Caroline Swineton was sentenced to 12-months imprisonment in 1857, the prison register recorded her crime as ‘indecent conduct’.[51] A brothel owner in Geelong, she was accused of attempting to prostitute her 10-year-old daughter outside the Theatre Royal in Melbourne.[52]

Anne Aitchinson was a ‘notorious and abandoned prostitute’ sentenced to three months or a £15 fine for using abusive and threatening language.[53] Seven days gaol was the punishment meted out to Jane Singleton and Honora Innes when they were caught fighting in the street.[54] Catherine Houston and Sarah Williams kept a ‘disorderly house’ in a laneway off Little Bourke Street, where a visiting constable witnessed dissipated groups of people singing obscene songs while Williams made indecent offers to men on the street. The pair were charged and found guilty of vagrancy and sentenced to six months with hard labour in the Western Gaol.[55]

Jane Smith and Anne Young were charged with robbery in January 1857: the victim, Mr Hamilton, had visited Anne’s house and found £21 missing after he left. This was known as bilking—robbery following a drunken seduction and/or paid sex. The defence argued that Hamilton was too drunk to remember where he lost the money. The robbery charges were dropped and instead the women were found guilty of vagrancy and sentenced to 12 months with hard labour. The defending lawyer objected, questioning the legality of changing the charge.[56] Victims of bilking were considered bad witnesses, as they were drunk when the alleged offences took place.

‘Vagrancy’ became a way of punishing the defendant without adequate proof. According to Catherine Colborne, the Victorian vagrant law was criticised for ‘both its breadth and vagueness’, which effectively made policing easier.[57] However, there was also a welfare aspect to police work, as arrest and incarceration for vagrancy could provide shelter for society’s most vulnerable.[58]

The gold rush offered new opportunities for Melbourne’s criminals and ex-convicts from Van Diemen’s Land, some opening brothels, recruiting orphan teenagers and taking on immigrant girls who came to the colony, friendless and without family.[59] Prostitution was a form of waged work that was always in demand in a city awash with money and men. Raelene Francis and Barbara Minchinton have written about the hierarchy within the sex industry in late nineteenth-century Melbourne. At the top were ornate brothels discretely serving the elite. At the bottom were the streetwalkers who may have had multiple clients and bilked.[60] Those on the middle and upper rung of the sex trade were less likely to enter the prison system.[61] The women who worked the streets in the gold rush period and frequently drew attention to themselves by being drunk, loud, disruptive or ‘in your face’ were more likely to find themselves in the Western Gaol. If the brothel owner and the women were discreet, they could escape the attention of the authorities, or they could simply pay a fine and move on. Henrietta Hall, described as ‘one of the most stylish and well-known habitues of this classic location’, was charged with running a disorderly house in La Trobe Street. The magistrate found no evidence of public indecency and advised her to run her establishment in an orderly manner.[62] By contrast, Joannah Brown, found to be operating a ‘notorious house of ill-fame’ in Johnston Street, Fitzroy, upset the neighbours by being disorderly in a public street and was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment in the Western Gaol.[63]

Nagy and Piper argue that women were overwhelmingly found guilty of minor public order offences from the 1860s. Theft was the next most frequent offence. Crimes of violence were less common.[64] The women in the Western Gaol during the 1850s appear to fit this pattern. In 1855, only 25 of the 1,162 offences and committals for the Western Gaol recorded carried a sentence of more than 12 months.[65] The same women moved in and out of the gaol on a regular basis serving short sentences.

The gaol routine

The women entered the Western Gaol through a door set into the red brick wall on Collins Street. It was an unprepossessing place that few Melbournians were aware of, unlike the bluestone Melbourne Gaol, which loomed over the city on the Russell Street hill. On admittance, the women were searched by one of the female turnkeys and their outer clothes removed, presumably to search for tobacco or alcohol. This process is described by a Mrs Taylor who charged Detective Mainwaring in the County Court for false imprisonment in 1862. After a night in the watchhouse, she was thrust into the Western Gaol with ‘drunken wretches’ and forced to strip half naked. When she objected, she was told by the turnkey that all were ‘guilty until proven innocent’.[66]

Women were given a classification and allotted to one of the whitewashed association wards where they would sleep. The classifications were determined by the severity of the sentence and the crime committed. The separation of prisoners into different classes was seen as a means of preventing ‘contagion’ between hardened criminals and younger offenders. Prisoners who had committed felonies and had longer sentences, described by Farie as the ‘worst ones’, were kept in separate ward with an airing yard. The next ‘worst’ group were in the next ward, and so on.[67]

Farie reported on the gaol’s first year of operation in the 1855 Blue Book (Figure 5), the annual record of statistical returns from government departments.[68] The women slept on the floor in the whitewashed ward they were assigned to. They were issued with two blankets and a rug each, as well as two sets of clothing. The medical officer visited every second day and religious services, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, were held every Sunday; non-denominational services were held on Fridays. The women received daily rations, as determined by their designated class. They were released from their wards at daybreak and laboured and exercised until 5 pm in winter or 6 pm in summer, when they were returned to their wards. Women were employed doing their own washing, making their own clothes, cooking and keeping the gaol clean.[69]

Figure 5: Extracts from the Gaol Returns submitted by Claud Ferie. PROV, VPRS 943/P0, Blue Book no. 5, 1855, p. 780.

The privileges prisoners received depended on whether they were short- or long-term prisoners. Short-term prisoners could receive deliveries of clothes and food from the outside once they had been examined by the officers, and letters could be sent and received quarterly. Prisoners sentenced to hard labour received ‘no such indulgences’.[70]

Visiting justice’s reports (Figure 6) recorded the movement of prisoners in and out of Melbourne gaols on a monthly basis. They also showed the numbers sentenced to imprisonment only, hard labour and those awaiting trial as well as other categories such as ‘lunatics’, the sick and destitute. Numbers in the gaol fluctuated between 90 and 150 at any one time, inflated by children accompanying their mothers. No children were recorded in the total of 92 prisoners and 11 ‘lunatics’ on 3 December 1855.[71] In January 1856, there were 106 people in the gaol—78 prisoners, 9 ‘lunatics’ and 13 children.[72] The numbers reached 147 the week of 21 December 1857 and included 118 women and 29 children.[73]

Figure 6: Visiting Justices Report for City of Melbourne Gaols for the month of April 1856. PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 56/3913.

Hard labour

Farie was unable to find employment for women sentenced to hard labour. They were ‘not of the class of women to do fine sewing’ and the fluctuating gaol population made it difficult to train women and develop the type of labour system common in other penal establishments.[74] The Public Works Department’s suggestion that women sentenced to hard labour should be employed in a laundry washing male prisoners’ clothes was dismissed as being too expensive. The site was too small and a laundry would require even more drainage work. Likewise, making shirts and clothes for male prisoners would require separate workrooms, as the women could not use their sleeping rooms as day rooms. What was required, the sheriff concluded, was a purpose-built female penitentiary.[75] The tantalising promise of a female penitentiary or laundry complex for women at Pentridge can be found in correspondence whenever conditions at the Western Gaol were criticised.[76]

Not being able to undertake hard labour disadvantaged female prisoners, as they were unable to apply for early release under the reward for labour regulations. In Melbourne Gaol, men received credits for working on the gaol building, assisting the officers or acting as wardens or cooks, and these credits could reduce their sentences.[77] For a brief period, women worked sewing flannels for the Penal Department, but it was not enough to generate labour hours.[78] Farie found this unfair and supported petitions requesting early release. Ann Plunkett was 16 when she helped her mother rob a lucky digger of 7 ounces of gold and £26 after drugging him with gin and milk and dumping him outside their lodging house. Ann was sentenced to three years hard labour. Farie supported the reduction of her sentence by three months due to her good behaviour.[79] Sarah Middle and her husband received a five-year sentence for receiving stolen goods. He was awarded a ticket of leave and released early. She was not able to earn this benefit, and Farie argued that this was unfair.[80] Both petitions were successful.

The lack of work meant that the women spent most of their daylight hours in the airing yards. Once their chores around the gaol were complete, their time was their own. This was a source of concern to the government, as prison theory argued that regular and full employment was the best means of delivering discipline and reform in the penal system.[81]

Discipline

Women prisoners were supervised by female officers. In 1858, the sheriff employed a gaoler, a senior female turnkey and three female turnkeys at the Western Gaol. A male turnkey was employed to supervise the male ‘lunatics’ who were housed at the gaol before transfer to Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum.[82]

Little is known of staff–inmate relationships. Prison theory sought to segregate prisoners from human contact, whether between fellow prisoners or between staff and prisoners.[83] However, in practice, human contact was unavoidable. A certain degree of familiarity would inevitably develop in a gaol so crowded and where women shared wards and moved in and out of gaol so frequently. Although formal power lay in the hands of the gaolers, order was as much dictated by the inmates, whose response to rules could determine whether order or instability reigned. Informal patterns of social accommodation—the bending of rules and building of personal relationships—could ensure voluntary compliance. How the women felt about their situation is unrecorded; however, their behaviour suggests that they found ways to accommodate their incarceration and the prison rules.

The Western Gaol was overcrowded, the women lacked work and, according to Youl, were ‘the most abandoned women on the world’.[84] Yet, he reported, ‘there is little to complain about the women’.[85] Youl was responsible for authorising the most severe punishment, solitary confinement in one of the stone cells. In his evidence to the 1857 penal discipline committee, he reported that he only had to inflict such punishment one or two times a year. He also reported that the women did not fight among themselves.[86] Dr Youl’s monthly reports included a few brief paragraphs describing the behaviour of prisoners in the different gaols. A typical report from March 1857 read: ‘The Female Gaol. Women good, the gaol greatly crowded a considerable number of children are confined with their parents.’[87]

It was only the ‘old hands’—that is, the ex-convicts—who swore and caused disruptions.[88] The ‘most notorious woman in Melbourne’, Vandemonian ex-convict Winifred Johnston, arrested for being drunk and disorderly and suspected burglary, made her escape in December 1856 by removing bricks from her solitary cell, climbing though the high windows and over the brick wall.[89] She was arrested the next day at The Gap on the way to the goldfields. At court, Johnston cross-examined Mr Gale, the gaoler, and remarked that ‘the people at the Western Gaol were not remarkable for being vigilant’.[90]

Most prisoners appeared to keep a low profile, their transgressions hidden or ignored. At times, their friends outside made contact. Bridgit Doyle was given a caution for trying to pass tobacco to a prisoner being transferred to the Western Gaol from the Supreme Court.[91] Ann Thorp was fined 40 shillings for passing tobacco to prisoners.[92] Youl advised that children living in the gaol with their mothers could not be allowed to exercise in the streets because their mothers would send them out to buy gin and tobacco.[93] Elizabeth Turner was fined 20 shillings for ‘holding communication’ with inmates of the gaol.[94] On her release from gaol in December 1857, Emma Ryan, alias Emma Williams, was accused of violently assaulting a drunken Thomas Cox and stealing his watch in Stephen Street. Cox reported that he ‘got acquainted’ with Emma in the gaol where he had worked as a carpenter. The jury found her not guilty.[95]

Children

In England during the nineteenth century women sentenced in local gaols to short sentences took their babies to gaol and left their older children with grandparents, siblings, partners, friends or neighbours.[96] Melbourne was a city of strangers, family connections were distant and most women with children in the gaol had been deserted by the children’s fathers.[97] Therefore, out of necessity, some mothers took their babies and young children to gaol. Children aged under six received a daily ration of wheaten bread, fresh meat, milk and soap. The presence of children in the gaol distressed and angered Youl. In his April 1856 report, he wrote that the children in the gaol were in a deplorable state and would become ‘animals’ if they were not provided with education.[98] There were 83 prisoners and 30 children in the gaol that month. To drive home his point, Youl attached a chart showing that 21 of the children were aged under eight (Figure 7).[99]

Figure 7: Return of children confined to the Female Gaol, Melbourne, 30 April 1856. PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 56/3913.

Some older children found wandering the streets of Melbourne were arrested and sent to join their mothers in gaol. Will and James Connelly were charged with vagrancy in 1858 and joined their mother who was serving a term of 12 months.[100] Jane Simmons was only three and a half when she was arrested with her sisters Harriet Pickering, aged five and a half, and Margaret Pickering, aged six. They were charged with being idle and disorderly or having no means of support. They joined their mother, Ann Curran, in the Western Gaol.[101] Dr Youl described having a young boy approach him and ask him to ‘have the kindness to send him to the female gaol’.[102] His mother and sister were in gaol for drunkenness. He told Youl that many of his friends had been in gaol with their mothers.[103]

Orphaned, abandoned or destitute children were also sent to the Western Gaol. A little boy in Collingwood was arrested for stealing bottles in May 1856. His destitute, widowed mother had seven children, all in poor condition. He was sent, weeping to the Female Gaol.[104] Another boy, both parents dead, was held in remand at the gaol until he could be admitted to the Orphan Asylum after he was caught stealing wood.[105] A 10-year-old boy from Castlemaine whose father was in a lunatic asylum was sent to Melbourne by the police; with nowhere to place him, he was put in the Female Gaol.[106]

Farie recruited educated prisoners when he could to teach the children to read. The children were separated from the convicted women and kept with the women on remand during the day.[107] Farie responded to Youl’s complaints by arguing that a children’s reformatory should be built; however, until then they had to be imprisoned with their mothers or else they would be ‘left on the street’.[108]

What impact the presence of babies and children had on relationships in the gaol on a day-to-day basis is not recorded. The children’s behaviour is not commented on in the visiting justices’ reports, suggesting that some kind of order was maintained by the women. How the children experienced the gaol is also not known, which is not surprising as children’s voices are often the most silent in the historical record.[109] The boy who pleaded with Youl to be sent to the gaol suggests that it was not a place to be feared—or, perhaps, that it was less fearful than life on the streets.[110]

The hospital ward

A small room was set aside in the gaol as a hospital. Its patients included prisoners who were sick, women suspected of insanity who were held for seven days for medical assessment, and women brought to the hospital destitute and unwell. Dr McCrae visited the Western Gaol at least once a week. A dispenser visited once a day with medicines and a nurse tended the patients.

According to the 1855 Blue Book, the disease most prevalent among the prisoners was ‘nerves and brain’, indicative, perhaps, of excessive alcohol, an existing condition or the psychological effects of trauma.[111] The chief medical officer’s report for 1857 noted that there were, on average, 148 people held in the gaol daily and that their illnesses were minor, the most common being dysentery, bronchitis, indigestion and diarrhoea. Dr McCrae wrote that ‘many of the complaints were of a trifling nature, but females are fond of medicine and if they were allowed to have it as they wished they would always be dosing themselves’.[112] Possibly this was an example of nineteenth-century medical gender bias—the dismissal and trivialisation of women’s symptoms by doctors.[113]

Coronial inquests were always held when a death occurred in prison. The women who died at the Western Gaol were generally not those serving sentences, but women admitted as ‘lunatics’ to be assessed or those in the last throes of illness. Many of these died in the most tragic of circumstances. Isabella Ham, the wife of a labourer on the goldfields, was admitted to the Western Gaol for ‘lunacy’. After being treated by Dr Webster, she was released. Three days later, she returned and gradually ‘sunk from the world’. She died from ‘disease of the brain’ aged 35.[114]

Alcohol and disease killed 42-year-old Mary Smith, also known as Sarah Bolton, in 1856. Arrested for vagrancy, this was Mary’s eleventh stint in gaol in the last 18 months. Suffering from a syphilitic disease, she was ‘completely out of her mind’ in her last days. The subsequent inquest determined that she died from apoplexy caused by ‘intemperance and dissipation’.[115]

One of the deaths listed in the 1857 chief medical officers report was of Catherine Sandey, a destitute and deserted woman who was sent to the Western Gaol for a medical assessment. En route from Port Albert, Gippsland, her infant son choked to death. In the Western Gaol she stole a bottle of disinfectant and poisoned herself before she could be admitted to the Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum.[116] Polly Tyrrell had handed her two-week-old baby to a stranger before being found intoxicated and arrested for child desertion. She was suffering an abscess on her breast and unable to feed, so an inmate acted as the baby’s wet nurse until the baby died from ‘derangement of the digestive system’.[117]

Former inmates returned to the prison when they or their children were seriously ill. Mary Clarke, a former inmate, was destitute, her husband in the Melbourne Hospital, when she requested entry to the Western Gaol. She died of dysentery after treatment aged 54.[118] Seven-month-old Charles Higgins, suffering dysentery, was handed over to nurse Ellen Perkins when his mother Elizabeth was admitted to the gaol. He died two days later in his mother’s arm. The gaol was praised for its kindness to Elizabeth.[119] Mary Edwards, a destitute, deserted and emaciated 40-year woman old broke windows to gain admittance to the gaol. Sent to the hospital, she died of tuberculosis.[120]

Catherine Coleborn argues that the ‘ad hoc welfarism’ operating in gaols in the 1860s and 1870s meant that the destitute, elderly and infirm, once they were fed and allowed to rest, had a better chance of survival in gaol than on the streets.[121] This was also the case in the 1850s when Melbourne’s only public hospital, built in 1846–48, could not cope with the demand generated by the gold rush population.[122]

A new system of seeking refuge

In December 1857, the Age reported that a woman called Buckly (also Buckley), a widowed mother with an infant and ‘a constant customer at the female gaol’, presented herself to the magistrate, declaring herself a vagrant without means of support.[123] The judge issued a warrant stating that she was sentenced to three months hard labour at the Female Gaol. Buckley then escorted ‘herself to gaol’.[124] This, the journalist reported, was ‘a new way of seeking refuge’.[125] Buckly was an old hand, having been imprisoned seven times previously. She entered the gaol where her behaviour was described as ‘indifferent’.[126]

Between 1854 and 1858, Melbourne was still a frontier town. Social welfare, such as it was, was provided piecemeal by a handful of private charities sponsored by churches and dependent upon donations. It was not until the late 1850s/early 1860s that asylums specifically for homeless woman and their children, known as industrial schools, were established.[127] The poor and destitute in Victoria had no right to relief, there were no poor laws, and unrepentant prostitutes and criminals were unlikely to elicit sympathy from the largely middle-class charity workers. The confidence with which Buckley, her new baby in her arms, approached the bench and sought access to the Western Gaol suggests this was an accepted means of survival when you were desperate.

There is no evidence to suggest that imprisonment in the Western Gaol deterred women from committing crimes or misdemeanours. Women moved in and out of gaol with such rapidity that there was little chance of reform. The labour tasks, such as they were, were not onerous. Zedner reached the same conclusion in her study of Tothill Gaol, Westminster, in the 1860s, arguing that gaol was seen as a place of refuge; a sentence of a few days at Tothill was ’a chance of a brush and wash up’.[128] Likewise, at the Western Gaol, the cost of briefly losing your freedom was worth paying when the outcome was food, shelter, clothes, a bath, medicine and time to recover from the effects of alcohol and the threat of violence on the streets.

The Western Gaol was also a communal female space that could be shared with your mother, sister or child, friends and co-offenders. Women, especially those combining theft and prostitution, often worked in pairs, and a ‘culture of female reciprocity’, which may have included friendships and a sense of family, developed.[129] Alana Piper has argued that the absence of men in the lives of female prisoners in the late nineteenth century resulted in the formation of female-centred households.[130] It is possible that similar types of quasi-familial relationships developed among women in gold rush–era Melbourne where the desertion of wives and children was common. The damp and miserable location of the gaol was always criticised by its administrators; however, it was also clean and well run.[131] Women who may have lived on emigrant ships, in convict settlements, or in Melbourne’s polluted and overcrowded Ianeways in tents or wooden cribs, were, perhaps, accepting of such discomforts.

Conclusion

Archival records suggest that the Western Gaol provided both welfare and punishment in gold rush–era Melbourne, and that it served an important role in providing shelter to a range of vulnerable women and children, including new mothers and babies, the homeless, alcoholics and the sick. Although prisoners lost their freedom, they received in return a form of welfare and support that was not available to them outside the prison walls.

The archive provides a tantalising glimpse into the workings of the gaol, but it tells us little of the private lives of its inmates. What did the women do in those hours in the yard or locked together in the sleeping wards? Some answers may emerge through historical archaeology, as it has in other colonial sites of incarceration and refuge.[132] The archaeological excavation of 600 Collins Street in 2023, the site of the former Western Gaol, uncovered a bluestone water tank, most likely part of the 1850s drainage works at the gaol. The artefacts excavated include women’s and children’s shoes, syringes, roughly cut beef bones, smoking pipes and sewing materials. The ubiquitous Melbourne oyster shells and ceramics, common in other Melbourne archaeological excavations, were absent, suggesting this was not a domestic site. The assemblage is currently being catalogued and analysed and may give us more insight into the women and children who found both a place of incarceration and refuge in the Western Gaol.[133]

Endnotes

[1] ‘Penal discipline’, Argus, 12 September 1857, p. 8.

[2] ‘Penal discipline’, Argus, 1 December 1856, p. 6.

[3] Ross McMullin, ‘The impact of gold on lawlessness and crime in Victoria 1851–1854’, Victorian Historical Journal, vol. 48, no. 2, May 1977, pp. 124–125.

[4] ‘Melbourne’, Geelong Advertiser, 28 October 1851, p. 2.

[5] ‘The gaols’, Argus, 23 January 1856 p. 5.

[6] G Davison, ‘Gold-Rush Melbourne’, in Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook and Andrew Reeves (eds), Gold: forgotten histories and lost objects of Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, p. 53.

[7] Christina Twomey, Deserted and destitute: motherhood, wife desertion and colonial women, ASP, Melbourne, 2002.

[8] Janet McCalman, Vandemonians: the repressed history of colonial Victoria, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2023, p. 108.

[9] G Serle, The golden age: a history of the colony of Victoria, 1851–1861, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Victoria, 1977, p. 191.

[10] ‘610 Collins Street (H7822-1688)’, Victorian Heritage Inventory, Victorian Heritage Database, available at <https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/209648>, accessed 5 April 2025.

[11] McCalman, Vandemonians.

[12] Raelene Frances, Selling sex: a hidden history of prostitution, NSW Press, Sydney, 2017, pp. 129–132.

[12] Barbara Minchinton and Sarah Hayes, ‘Brothels and sex workers: variety, complexity and change in nineteenth-century Little Lon, Melbourne’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 51, no. 2, 2020, pp. 165–183.

[13] Catharine Coleborne, Vagrant lives in colonial Australasia: regulating mobility, 1840–1910, Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2024, pp. 61–67.

[14] Caroline Ingham, ‘“There not being any place to keep her”: incarcerating women in nineteenth-century Western Australia’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 158–177; Mark Finnane, Punishment in Australian society, Oxford University Pres, Melbourne 1997, p. 40.

[15] PROV, VPRS 516/P0 Central Register of Female Prisoners. For example, Alana Jayne Piper and Victoria M Nagy, ‘Risk factors and pathways to imprisonment among incarcerated women in Victoria, 1860–1920’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 42, no. 3, 2018, pp. 268–284; Victoria Nagy, ‘Women, old age and imprisonment in Victoria, Australia 1860–1920’, Women and Criminal Justice, vol. 30, no. 3, May 2020, pp. 155–171; Alana Piper, ‘“I go out worse every time”: connection and corruption in a female prison’, History Australia, vol. 9, no. 3, 2012, pp. 132–153; Alana Jayne Piper and Victoria Nagy, ‘Versatile offending: criminal careers of female prisoners in Australia, 1860–1920’, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 48, no. 2, Autumn, pp. 187–210.

[16] Meighen Katz, ‘City of women: the old Melbourne gaol and a gender-specific interpretation of urban life’, in Jacqueline Z Wilson, Sarah Hodgkinson, Justin Piché and Kevin Walby (eds), The Palgrave handbook of prison tourism, Palgrave McMillan, London, 2017. p. 345; Old Treasury Museum, ‘Female felons: the stories behind the women. Crime in the city’, available at <https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Female-Felons-reduced.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOopovAULL99UE5bKA5ohHAJJKxyOqdHu4Hl84-YvX6jBlWEC1AX1>, accessed 4 February 2025.

[17] Lucia Zedner, Women crime and custody in Victorian England, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991, p. 132.

[18] McCalman, Vandemonians; Clare Anderson, Subaltern lives: biographies of colonialism in the Indian Ocean world, 1790–1920, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012.

[19] PROV, VPRS 12941/P1, (1853–1857) Register of Female Prisoners Received.

[20] PROV, VPRS 516/P0, 1-750 (1855–1861) Central Register of Female Prisoners.

[21] Piper and Nagy, ‘Versatile offending’, p. 187.

[22] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/VPRS1189>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[23] ‘Mr Claud Farie, late sheriff of Melbourne’, Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 10 September 1870, p. 157.

[24] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Age, 7 November 1854, p. 5; Ann M Mitchell, ‘Youl, Richard (1821–1897)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/youl-richard-4900/text8201>, published first in hardcopy 1976, accessed 26 January 2025.

[25] See PROV, VPRS 24 Inquest Deposition Files, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/VPRS24>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[26] Keith Pescot, A place to lay my head: immigrant shelters of nineteenth-century Victoria, ASP, Melbourne, 2003, p. 4.

[27] Robert Hoddle, Melbourne – Port Phillip – 1840 from Surveyor-General’s Yard, art original at State Library Victoria, accession number H258, available at <https://find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/1sev8ar/alma9916544173607636>, accessed 24 November 2024.

[28] PROV, VPRS 4/P0, Folder No: 33A, 1839/33A; Plan for a temporary gaol at Melbourne signed by James Rittenberg, clerk of works, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/575A30C5-F7F4-11E9-AE98-238E5E6F13F0?image=1>.

[29] PROV, VPRS 19/P0, file 42/1935, Reporting upon the state of the treadmill, clerk of works, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/E2382540-BD5A-11ED-8BFF-21B5E274EA80?image=1>; PROV, VPRS 19/P0, file 43/1878, Approving of the acceptance of the tender by Langlands, Fulton & Co for the repair of the treadmill, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/14B604A7-BD5B-11ED-8BFF-0F144D129765?image=1>.

[30] PROV, VPRS 19/P0, 44/206, In answer to letter with reference to the use to be made of the present temporary jail on the occupation of the new building, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/0F243555-BEE6-11ED-8BFF-BFB3BE91BFA5?image=2>; PROV, VPRS 19/P0, file 46/956, States that he has handed over the old jail and mill house to the military, clerk of works, Melbourne, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/BDE7C8AE-C45D-11ED-8BFF-094872EC28AD?image=2>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[31] ‘Collins Street: some early memories’, Argus, 25 June 1927, p. 6.

[32] ‘House of correction’, Female Convicts Research Centre, available at <https://femaleconvicts.org.au/convict-institutions/gaols-in-vdl?view=article&id=443:houses-of-correction&catid=99>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[33] Colin Rimington, History of the criminal justice system in Victoria, Hybrid Publishers, Melbourne, 2023, pp. 82–83.

[34] William Westgarth, ‘Prison discipline progress report 1852’, Parliament of Victoria, 1852, p. 5, available at <https://webresource.parliament.vic.gov.au/VPARL1852-53Vol2p407-417.pdf>, accessed 27 January 2025.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid. p. 5.

[37] ‘Supplementary estimates’, Argus, 8 December 1852, p. 5; ‘Supplementary estimates’, Banner, 11 November 1853, p. 7.

[38] ‘Local intelligence’, Banner, 10 March 1854, p. 9; ‘Advertising’, Argus, 9 May 1854, p. 1; ‘Advertising’, Argus, 3 November 1855, p. 7; ‘Government notifications’, Age, 31 October 1855, p. 5.

[39] PROV VPRS 8168/P3, MELBRL 12; MELBOURNE, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/B4E54AAB-F83D-11E9-AE98-43537B60CEAE?image=1>.

[40] PROV, VPRS 943/P0, Blue Book no. 5, 1855, pp. 745–780, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/531389DF-F424-11E9-AE98-7FBBFA7B76C8>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[41] PROV, VPRS1189/P0, file 56/3913, Visiting Justice Report April 1856, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/18FD51DD-F426-11E9-AE98-F5C091CCADB4>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[42] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 56/6910, Visiting Justice Melbourne Report July 1856, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/18FEB16E-F426-11E9-AE98-EBF54AB40DBB>; PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 56/5090, Submitting requisition for the repair of water tanks at the female gaol, 19 June 1856, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/18FD51DD-F426-11E9-AE98-F5C091CCADB4>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[43] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 57/3724, Visiting Justice Melbourne Report April 1857, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/19047DD2-F426-11E9-AE98-0F78875F2DF4>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[44] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 57/6029, Visiting Justice Melbourne Report July 1857, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/190715E4-F426-11E9-AE98-E90E740BC9F7>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[45] Ibid.

[46] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, 57/4024 Death of Mr Abbot, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/1922B449-F426-11E9-AE98-B3B4D3D98634>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[47] Twomey, Deserted and destitute, p. 84.

[48] Coleborne, Vagrant lives, p. 30.

[49] No. 22, ‘Act for the Better Prevention of Vagrancy and Other Offences’, Supplement to the Victorian Government Gazette, 5 January 1853, <https://gazette.slv.vic.gov.au/view.cgi?year=1853&class=A&page_num=1&state=V&classNum=A3&id=>.

[50] Criminal statistics: return of prisoners arrested by the Victorian Police Force during the half year ended 31 December 1858 presented to both houses of parliament by his excellency’s command, John Ferries Government printer, Victoria, 1859, available at <https://webresource.parliament.vic.gov.au/VPARL1859-60No23.pdf>, accessed 26 January 2025

[51] PROV, VPRS 516/P0, 1-750 (1855-1861), no. 17 Caroline Swineton, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/221A1D5E-F3A9-11E9-AE98-87F4AD50F5F0?image=19>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[52] ‘Police’, Age, 2 May 1857, p. 6.

[53] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Age, 29 December 1854, p. 5.

[54] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Argus, 21 January 1856, p. 5.

[55] ‘Police’, Age, 17 June 1857, p. 6.

[56] ‘Police’, Argus, 30 January 1857, p. 6.

[57] Coleborne, Vagrant lives, p. 80.

[58] Ibid. p. 58.

[59] McCalman, Vandemonians, p. 124

[60] Frances, Selling sex, pp. 129–132.

[61] Minchinton and Hayes, ‘Brothels and sex workers’, p. 181.

[62] ‘The Latrobe Street fair’, Age, 6 March 1856, p. 2.

[63] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Argus, 5 February 1856, p. 5.

[64] Victoria Nagy and Alana Piper, ‘Imprisonment of female urban and rural offenders in Victoria, 1860– 1920’, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, vol. 8, no. 1, 2019, p. 103.

[65] ‘The gaols’, Argus, 23 January 1856, p. 5.

[66] ‘What may happen to a woman in Melbourne’, Herald, 1 May 1862, p. 5.

[67] ‘Minutes of evidence Claud Farie’, 21 January 1857, in Report from the Select Committee on Prison Discipline, Vic. LAV&P, 1856–1857, p. 5.

[68] PROV, VPRS 943/P0, Blue Book no. 5, 1855, pp. 745–780.

[69] Ibid., p. 781.

[70] Ibid., p. 779.

[71] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Argus, 3 December 1855, p. 6.

[72] ‘Local intelligence’, Age, 8 January 1856, p. 2.

[73] ‘The Melbourne gaols’, Age, 21 December 1857, p. 5.

[74] ‘Minutes of evidence Claud Farie’, p. 2.

[75] PROV, VPRS1189/P0, file 56/410, Visiting Justice Report March 1856, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/18FC406C-F426-11E9-AE98-614937E9C42A>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[76] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 57/6029 Visiting Justice Report July 1857, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/190715E4-F426-11E9-AE98-E90E740BC9F7>, accessed 4 April 2025; PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 57/1189 Sherriff Report 26 August 1857, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/19017090-F426-11E9-AE98-C763955F5E48>, accessed 4 April 2025; Report from the Select Committee on Prison Discipline, Vic. LAV&P, 1856–1857, p. 18.

[77] ‘Minutes of evidence Claud Farie’, p. 1.

[78] Ibid., p. 2.

[79] PROV, VPRS1189/P0, file 57/7884, Forward Anne Plunkett Petition, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/192C2A30-F426-11E9-AE98-07057E7945D8>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[80] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 57/2400, Sarah Middle Petition, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/1929921E-F426-11E9-AE98-1BC73921F7AA>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[81] ‘Penal discipline’, Argus, 12 September 1857, p. 8.

[82] PROV, VPRS 943/P0, Blue Book no. 5, 1855, p. 782

[83] Zedner, Women crime and custody, p. 150.

[84] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, 21 January 1857, in Report from the Select Committee on Prison Discipline, Vic. LAV&P, 1856–1857, p. 82.

[85] Ibid., p. 83.

[86] Ibid., p. 1.

[87] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 57/2971, Visiting Justice Report March 1857, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/achive/19047DD2-F426-11E9-AE98-0F78875F2DF4>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[88] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, p. 88.

[89] ‘A hint for the puddlers’, Bendigo Advertiser, 24 December 1856, p. 3; ‘A female prison breaker’, Portland Guardian and Normandy Gazette, 26 December, p. 2. For Winifred Johnston’s biography see McCalman, Vandemonians, pp. 131–132.

[90] ‘Crown land sales’, Argus, 23 December 1856, p. 5.

[91] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Age, 5 February 1855, p. 5.

[92] ‘Domestic intelligence’, Argus, 15 March 1855, p. 5.

[93] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, p. 88.

[94] ‘The city and suburbs’, Age, 26 April 1856, p. 5.

[95] ‘Criminal sessions’, Age, 19 December 1857, p. 5.

[96] Helen Johnston, ‘The imprisoned mother in Victorian England 1853–1900: motherhood, identity and the convict prison’, Criminology and Justice, vol. 19, no. 2, 2019, p. 13.

[97] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, p. 92.

[98] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0, file 56/3913, Visiting Justice of Penal Establishments Report, April 1856, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/18FD51DD-F426-11E9-AE98-F5C091CCADB4>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[99] Ibid.

[100] ‘City court’, Age, 19 October 1858, p. 6.

[101] PROV, VPRS 516/P0, 1–750 (1855–1861): no. 259 Ann Conner, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/221A1D5E-F3A9-11E9-AE98-87F4AD50F5F0/content?image=266>; no. 265 Margaret Pickering, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/221A1D5E-F3A9-11E9-AE98-87F4AD50F5F0/content?image=272>; no. 272 Harriet Simmons, <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/221A1D5E-F3A9-11E9-AE98-87F4AD50F5F0/content?image=279>; no. 273 Jane Simmons, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/221A1D5E-F3A9-11E9-AE98-87F4AD50F5F0/content?image=280>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[102] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, p. 93.

[103] Ibid.

[104] ‘Local intelligence’, Age, 20 May 1856, p. 3.

[105] Ibid.

[106] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, p. 92.

[107] ‘Minutes of evidence Claud Farie’, p. 5.

[108] PROV, VPRS1189/P0, file 56/10377, Visiting Justice of Penal Establishments Report, October 1856, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/18FFE9EF-F426-11E9-AE98-ED5CDA31953F>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[109] Jennifer Helgren and Colleen A Vasconcellos (eds), Girlhood: a global history, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, 2010, p. 4.

[110] ‘Minutes of evidence Dr Youl MD’, p. 92

[111] PROV, VPRS 943/P0, Blue Book no. 5, 1855, p. 780.

[112] Chief Medical Officer, ‘Return of diseases in the various establishments under the charge of the chief medical officer in 1857’, John Ferres Government Printer, Melbourne, p. 6.

[113] Michelle Wisby, ‘How healthcare system designed “by men for men” is failing women’, News GP, 24 March 2024, available at <https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/professional/fixing-a-health-system-designed-by-men-for-men>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[114] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, 1856/67 Female Isabella Ham, Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/DC098345-F1BB-11E9-AE98-D1B47FF01F29?image=5>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[115] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, 1856/101 Female Mary Smith, Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/F97EB629-F1BB-11E9-AE98-1BB344F585BD?image=2>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[116] PROV, VPRS 24/0000, 1857/74 Female Catherine Sandey, Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/3CCD96E8-F1BD-11E9-AE98-F18CABE901C2?image=6>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[117] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, 1856/13 Female Ellen Tyrrell, Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/DC1DF5B5-F1BB-11E9-AE98-47F6B8A3DECB?image=7>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[118] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, 1856/119 Female Mary Clarke, Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/FC477376-F1BB-11E9-AE98-2F478FB5DA75?image=2>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[119] ‘Coroners inquests’, Age, 27 February 1857, p. 5; PROV, VPRS 24/P0, 1857/107 Male Edward Charles Higgins Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/1909D122-F1BC-11E9-AE98-7F8897DEB820?image=4>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[120] PROV, VPRS 24/P0, 1859/24 Female Mary Edwards: Inquest, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/BF3D2122-F1C0-11E9-AE98-4F72AFF92569?image=2>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[121] Coleborne, Vagrant lives, p. 82.

[122] Michael Cannon, Melbourne after the goldrush, Loch Haven Books, Arthurs Seat, 1983, p. 408.

[123] ‘The news of the day’, Age, 28 December 1857, p. 5.

[124] Ibid.

[125] Ibid.

[126] PROV, VPRS 516/P0, 1–750 (1855-1861): no. 25. Catherine Buckley, available at <https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/221A1D5E-F3A9-11E9-AE98-87F4AD50F5F0?image=27>, accessed 4 April 2025.

[127] Twomey, Deserted and destitute, p. 49.

[128] Zedner, Women crime and custody, p. 170.

[129] Alana Jane Piper, ‘Us girls won’t put another away’: relations among Melbourne’s prostitute pickpockets, 1860–1920’, Women’s History Review, vol. 27, no. 2, 2018, p. 11.

[130] Alana Piper, ‘“l’ll have no man”: female families in Melbourne’s criminal sub-culture, 1860–1920’, Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 39, no. 4, December 2015, p. 444.

[131] ‘The western gaol’, Argus, 10 May 1859, p. 5.

[132] Richard Tuffin, David Roe, Sylvana Szydzik, E. Jeanne Harris and Ashley Matic, Recovering convict lives: a historical archaeology of Port Arthur Penitentiary, Sydney University Press, 2021; Eleanor Casella, Archaeology of the Ross Female Factory: female incarceration in Van Diemen’s Land, Queen Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, 2002.

[133] Brendan Marshall, Grace O’Donoghue-Hayes, Isabella McVeigh and Sarah Miramset, ‘582–606 Collins Street (H7822-2422) Archaeological Report’, TerraCulture. In progress.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples