Last updated:

‘Bluestone sawing in Victoria: cutting a niche in the stone industry’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 22, 2025. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Susan Walter.

This is a peer reviewed article.

Bluestone is an iconic, durable and valuable Victorian building material, recognised in state and local heritage registers and overlays. In 2024, Malmsbury Bluestone became Australia’s first designated Global Heritage Stone Resource (GHSR) through UNESCO’s Heritage Stone Sub-Commission, managed by the International Union of Geological Sciences. A key factor in the success of the nomination was the wide use of the stone throughout Victoria, several other Australian colonies and New Zealand. This was driven by the introduction of stone sawing technology in Victoria in the 1860s by stonemasons Thomas Glaister and Thomas Gamon. These men were not only pioneers of the eight-hour day in Victoria, but also formed a little-known cooperative of masons who, working independently of capitalists, won some key government contracts for structures now listed on the Victorian Heritage Register. Their innovations in mechanical sawing of Malmsbury Bluestone enabled Melbourne’s streets to be paved with this durable stone, and their cooperative created jobs and exports and vertically integrated the industry to keep out the capitalists and uphold the quality of their work.

The social and cultural heritage of stoneworkers is inherent in the structures they create, as is their labour history, yet most heritage citations barely recognise the stone itself, let alone the labour of those who create the structures. Using Malmsbury Bluestone as an example, a focus on geoheritage via the GHSR designation program (in which stone is the centre of attention) uncovers the cultural and social history of the stones used to build cities, more so than concentrating on architecture alone. Glaister and Gamon might blur the lines between labour and capitalism, but they are also an example of the success of the eight-hour day. Their interactions with bluestone deserve more than a passing mention in Victoria’s built and cultural heritage.

Tom Griffiths posits in The Art of Time Travel that ‘the past is a quarry of ideas’.[1] It can also be argued that quarries themselves are wormholes into the past and are an essential factor in our ability to research, record, understand and acknowledge the significance of the stone industry in Australia’s history and structural heritage. One such wormhole was exposed during the author’s research into the industrial history of Malmsbury Bluestone, a basalt building stone sourced from a Victorian town about 100 kilometres north-west of Melbourne. In February 2024, this stone became Australia’s first designated Global Heritage Stone Resource (GHSR) through the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Heritage Stone Sub-Commission, managed by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).[2]

One of the key criteria for assessing a stone nominated for this designation is demonstrated wide usage, either by exporting to other countries and continents, or by distance. Another is the documented history of its use and the cultural and social significance of the structures that contain the stone. This geoheritage scheme works differently to the built heritage scheme typically used in Australia, especially at the state and local level, which tends to take one structure at a time and compare its value to a diverse range of themes. A GHSR designation places the focus on the individual stone, with nominations requiring a detailed history of the resource and the value of its heritage based on its entire use across multiple sites. In this way we can examine stone at a much broader level, understanding its significance to a nation’s stone industry, social and cultural history and built heritage.

The fact that Malmsbury Bluestone was exported from Victoria to several other Australian colonies, and to New Zealand and Calcutta (now Kolkata), is a direct result of technology introduced to Footscray in the 1860s by two key players—stonemasons Thomas Glaister and Thomas Gamon. In addition to becoming active members of the Operative Stone Masons Society, they formed a cooperative of fellow masons who won key government contracts, their goal being to work independently of capitalists. However, it was their innovation in the mechanical sawing of Malmsbury Bluestone that enabled the paving of Melbourne’s streets with this durable stone while also creating jobs and exports, and vertically integrating the industry to keep out the capitalists. This article, primarily using microhistory, examines the lives of these two men, their labour ideals, their industrial innovations and the development of the bluestone industry of which they were a driving force. It draws on public records held at Public Record Office Victoria (PROV), including land, statistical and other vital records. It also uses contemporary periodicals (newspaper and trade publications) and trade union and patent records.

In addition to any perceived architectural value, the stony history of Malmsbury Bluestone is inherent in the structures that stonemasons, including Glaister and Gamon, created; thus, corresponding statements of significance should be written with a full understanding of the industry and labour culture in which stonemasons and quarrymen worked, giving credit where credit is due. The author also considers arguments made at the time that Glaister and Gamon were just capitalists in disguise and were not genuinely wishing to improve the plight of labouring men.

Bluestone by necessity

The importance of bluestone to the development of greater Melbourne can easily be overlooked. A comprehensive history of this building material has never been written, but the stone often forms the foundation or fabric of other histories. First, we must acknowledge that many of the numerous architectural structures constructed with bluestone have been demolished and we can only view the remnants.[3] Second, we often overlook and take for granted the city’s everyday infrastructure—building foundations, gutters, kerbs, pitchers, paving and steps—that are frequently made of bluestone. The stone appears in many books on the history of Melbourne, often seen in the background, but not identified. For example, in Maie Casey’s Early Melbourne Architecture 1840–1888, bluestone appears in more photographs of buildings than the captions suggest, and sadly some of these have since been demolished.[4] Taking a more technical approach, in 1988 Alan Spry documented the various sources of stone, including bluestone, used in Melbourne in the nineteenth century, and published a long list of structures known to have utilised bluestone from 1838 to 1899.[5] With the advent of digital resources, such as those found on Trove, it is likely that Spry’s list is only the tip of the iceberg.[6] Tim Edensor’s 2020 ‘love letter to the city’, Stone: Stories of Urban Materiality, moves away from the focus on architecture and examines stone as a material, resulting in an eloquently expressed, detailed examination of history, texture, flow and the networks imbedded in the stone that makes our built environment and is reflected in our cultural commemorative heritage.[7]

While Melbourne was surrounded by bluestone sources, bluestone from Malmsbury and Lethbridge quarries was also freighted to Melbourne, and beyond, to be used in specific projects, many of which survive and are of state or local heritage significance. Freight costs were a major consideration in choosing which stones to use; however, the properties of the stone also had to suit the purpose, as did the cost of working the stone. Sandstone is easier to work but less durable, especially under wet conditions, while granite is durable but harder to work, thus attracting higher labour costs. Bluestone offered a ‘middle ground’ alternative, being durable in the wet and easier to work than granite.

There was some resistance to the use of bluestone due to its colour,[8] but Melbourne had limited local resources of lighter coloured stones that were of suitable quality; hence, sandstone was imported from Gariwerd/Grampians, Tasmania and Sydney, and limestone from New Zealand.[9] With respect to street paving, stone was imported from Scotland, with Castlemaine slate becoming an early local alternative.[10] An ideal stone would be one that was local, durable, easy to cut and slip resistant. Nature had provided bluestone; however, it required Victorians to be innovative enough to exploit its properties. This is where stonemasons Thomas Glaister and Thomas Gamon enter the story.

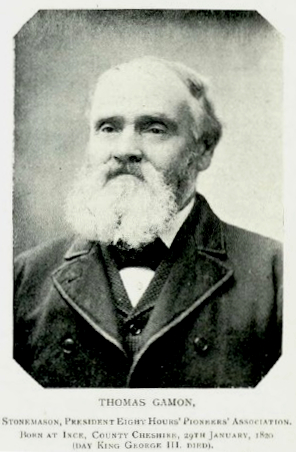

When Thomas Glaister and Thomas Gamon stepped off the Chalmers at Port Melbourne in November 1852, it is unlikely either of them anticipated the impact they would have in the development of their new home or the history of Victoria’s iconic bluestone building stone.[11] Glaister, aged 28, was from Cumberland. He was married with one child and another on the way, but travelling on his own.[12] Gamon, aged 32, was from Cheshire (Figure 1). He was also on his own and had reportedly been the foreman mason at the building of the Birkenhead Docks.[13] Both were stonemasons and their names adjoin each other on the passenger list. If they did not already know each other prior to departing London, they had plenty of opportunity to become acquainted on the long voyage. Gamon supposedly headed straight for the Fryers Creek diggings near Castlemaine, but Glaister’s movements are unknown for several years.[14]

Figure 1: Thomas Gamon (1820–1908), c. 1896, stonemason, member of the Operative Stonemason’s Society and president of the Eight Hours’ Pioneers Association. Source: WE Murphy, History of the eight hours' movement, Spectator Publishing Company, Melbourne, 1896, pp. 61, 80a.

Pushing rocks uphill

We may never know if either man had any previous background in campaigning for workers’ rights, but Glaister and Gamon certainly rocked the boat once they arrived back in Melbourne. Their names are briefly mentioned in WE Murphy’s first volume of the History of the Eight Hours’ Movement (1896) when Gamon was the president of the Eight Hours’ Pioneers Association, but it is rare to find other references to these men in related historical writings.

Glaister was an active member of the Operative Stone Masons Society by April 1856, and he served as secretary through 1859, although much of his activity has been poorly documented.[15] These activities meant he was regularly associating with fellow masons Charles Jardine Don, James Galloway and James Stephens, men who are still recognised for being similarly politically active.[16] In later life, Glaister stated that he had been an early supporter of the eight-hours’ movement but had been working in the country when most of the progress towards an eight-hour day was made in Melbourne.[17] Murphy recorded that Glaister was the marshal for the mason’s march through the streets of Melbourne in 1856, and newspaper articles reveal that he was involved in organising the monument to James Galloway in Melbourne in 1869.[18]

Building contractor William Croker Cornish is notorious for having refused to accept the eight-hour day during the construction of Melbourne’s Houses of Parliament.[19] After he joined with John Vans Agnew Bruce to construct the Melbourne–Sandhurst railway, Glaister helped to expose, in 1858, that Cornish and Bruce were encouraging more masons from England to seek work on Victorian railways.[20] This was with the express intention of further lowering local wages through the oversupply of labour. The masons also objected to Cornish and Bruce subcontracting work to other parties, a mechanism by which another level of profit had to be extracted from the fixed price of the total railway contract. However, as Rich explains in his analysis of the significance of the eight-hour day, James Stephens later stated that he had advocated for subcontracting and believed he had been vindicated for this stance.[21]

Glaister was present and offering support in January 1859 to stonemason John Newman who had been contracted in South Australia to work on the Geelong–Ballarat railway and was prosecuted by the contractors under the Masters and Servants Act for refusing to work under non-union conditions.[22] The Act used the term ‘artificer’ in the context of agricultural workers, and, in a previous case relating to compositors, had been deemed not to cover such workers.[23] However, the Geelong police magistrate took the view that the Act was not limited to agricultural artisans and Newman was sentenced to 24-hours’ imprisonment.[24] Calls for the Act to be repealed began soon after, with Glaister attending one public meeting on the subject.[25]

Cooperatives and capitalists

The timing of a significant action by Glaister and Gamon is probably more than coincidence. In March 1859, they formed their own cooperative, Thomas Glaister & Co., comprising some 40–50 stonemasons, stone merchants and contractors with the specific intention of winning government contracts in their own right.[26] This workers cooperative is mentioned, though not by name, in two significant works on labour history and cooperatives in Australia.[27] Coghlan’s monumental Labour and Industry in Australia (1918) says that it was formed ‘with the approval of their union’ and that ‘the success of the first association led to the formation of two others’.[28] Historians Greg Patmore, Nikola Balnave and Olivera Marjanovic cite Coghlan as their source for this cooperative being an example of ‘significant co-operative activity in the Melbourne building industry’ prior to 1860.[29] Unfortunately, Coghlan does not include his sources, so the additional two early building cooperatives may remain unidentified without further research.[30]

Historians Vern Hughes (1999), and Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic (2024), have analysed the role of cooperatives in Australia’s labour history from the perspectives of both production and consumption. Hughes defined a cooperative as ‘an autonomous association of persons which seeks to collectively provide some social or economic benefit for its members, usually through an enterprise or business venture’.[31] Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic define a cooperative as a member owned business that is ‘an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations, through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise’, and is based on ‘values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity’. They characterise a worker cooperative as an autonomous enterprise that ‘workers can become members of … usually through nominal holdings of share capital’; such members ‘receive a share of the income after the payment of material costs, and the co-operative principle of one vote for each member applies’. This is exactly what Glaister & Co. created.[32]

Hughes outlined three main phases of the development of cooperatives in Australia:

- 1860–90: mutual aid phase (exemplified by friendly societies, community settlement, retail cooperatives and mechanics’ institutes) aimed at transplanting capitalism

- 1915–22: reaction against the provision of welfare by the state phase

- late 1940s: postwar reconstructive phase.[33]

In their more recent analysis, Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic consider six key periods: pre-1860, 1860–90, 1890–1914, 1914–75, 1975–2009 and 2009–24. In doing so, they demonstrate that the 1975–2009 period was the peak of cooperatives in Australia.[34] They also demonstrate that, of the 10,451 cooperatives recorded by January 2024 in the Visual Historical Atlas of Australian Co-operatives, only 177 (i.e. less than 2 per cent) were worker cooperatives (with that figure including producer cooperatives), and most of those occurred after 1864. The role of cooperatives in saving jobs in times of unemployment is also highlighted by Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic.[35] Therefore, these studies demonstrate that Glaister & Co. is a rare example of an early worker cooperative in Australia.

The first contract awarded to Glaister and Gamon’s cooperative was in April 1859 for the entrance buildings and panopticon at Pentridge Gaol, the news of which, the Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle said, would astonish its readers.[36] The cooperative system permitted them to work independently of capitalist contractors whose need to make a profit put downwards pressure on labourers’ wages when costs blew out or delays occurred. Thomas Glaister & Co.’s cooperative model provided members with basic wages and allowed lower tender bids to be submitted, any profits being shared among the cooperative members. Under this model, Glaister & Co. won tenders and completed contracts for parts of Pentridge Prison (1859, 1861), Ararat Gaol (1859–61), the Melbourne General Post Office (GPO) (1860, 1862–65), the bluestone-lined Alfred Graving Dock (1864) (Figure 2) and a few private contracts, including a Chinese courthouse in Little Bourke Street.[37] These works incorporated the use of bluestone, sandstone and granite. In August 1859, the cooperative purchased land between Peel and Capel streets North Melbourne, which became their depot for several years.[38]

Figure 2: Alfred Graving Dock, Williamstown, in 1938. The bluestone-lined dock was partially built by Glaister & Co. PROV, VPRS 8362/P0001/58, 603.

Naturally, there were naysayers who were determined to see the cooperative fail or were convinced that its members were capitalists in disguise. When the cooperative was not successful in obtaining the contract for the Pentridge Prison boundary wall, it received more notice than when, shortly afterwards, it gained the contract for erecting Pentridge Hospital.[39] In January 1860, a member of the public called for the cooperative, which was now regarded as a contractor in its own right, to be expelled from the Masons’ Society.[40] A rumour then surfaced that the Masons’ Society itself had proposed to take such action; however, the society vehemently denied this and confirmed that it was in no way connected to the cooperative.[41] This appears to be the case, as Glaister had resigned from the Central Committee of the Masons’ Society in June 1859; by August he was described as its ‘late Secretary’.[42] However, membership of the cooperative was limited to Masons’ Society members; therefore, it was assumed that the cooperative was run by the society and that all of its members were stonemasons.[43]

Other commentators criticised the cooperative for subcontracting—an evil that capitalists were often accused of—including the excavation work for the GPO and iron foundry work at Pentridge. Yet, as Glaister argued, the cooperative only contracted out work when its own members did not have the necessary skills or resources, and any labour employed still worked under union conditions.[44]

By vertically integrating the main components of the stone industry into its business model, the cooperative could protect its operations from outside capitalists and maintain its good reputation. For example, taking over the leases of the quarries that supplied its stone meant that it could manage and maintain consistent levels of supply, quality and price. For these reasons, in 1860, Glaister & Co. took over the lease of the sandstone quarries at Point Ventenet and Spring Bay in Tasmania to ensure an ongoing supply of quality stone for the GPO contract, while also supplying stone to others.[45] Thomas Gamon lived in Tasmania between 1863 and 1865 in order to manage these quarries.[46] There is also evidence that the cooperative controlled bluestone quarries at Maidstone for the Graving Dock contract in 1865, which employed 170 men, and may have attempted to establish a sandstone quarry in Victoria.[47] This by no means amounted to a monopoly, as there were many bluestone quarries around Melbourne in addition to the stone imported from other Australian colonies and overseas.[48]

While Glaister had strong labour ties and sympathies, he occasionally ventured into the world of capitalists, becoming the employer, not the employee; however, in most cases, it was his fellow masons and associated tradesmen that reaped the rewards of his efforts: work and income at union-approved rates and conditions. His stated view on land policy was that, rather than sell land cheaply to benefit a few, the government should get a good price and use the funds to provide all Victorians with education and public transport.[49]

In April 1863, the original cooperative ceased, partly due to natural attrition through deaths and inability to work, and a new, smaller company was formed consisting of four members.[50] These were Thomas Glaister, Thomas Gamon and Leonard Carr, all original members, and stonemason Isaac Moore, a new member of the company.[51] It is possible that this group is the second of the three stonemasons cooperatives recorded by Coghlan. The sale of the cooperative’s depot land at North Melbourne between 1863 and 1867 probably enabled profits to be distributed among the members and permitted the next development in this story.[52]

Bluestone yields to technology

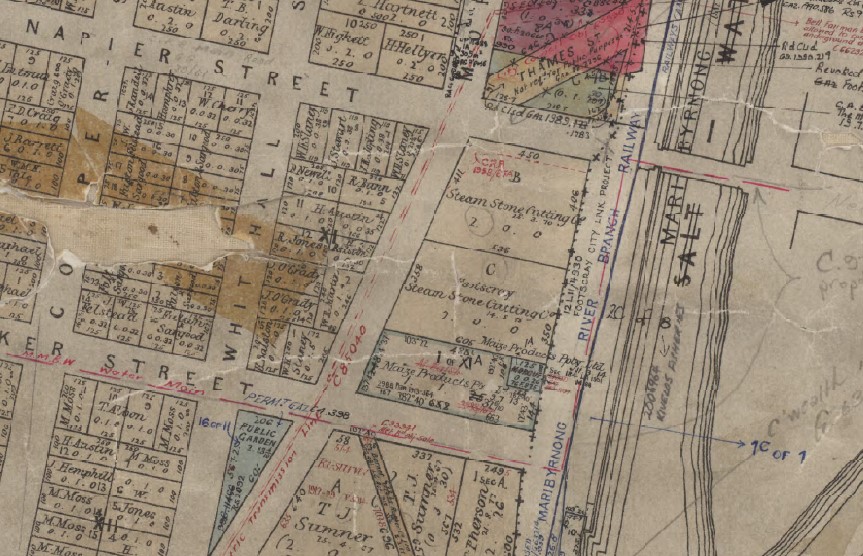

It was probably their use of massive quantities of bluestone in the early works for the Graving Dock at Williamstown that prompted the cooperative’s next move.[53] One of the perceived benefits of the eight-hour day was the extra time available to workers to ‘improve themselves by study, education and the acquisition of culture’.[54] While there were concerns that workers would use this time drinking in taverns, Glaister, a declared non-drinker, was clearly not one to do so.[55] In 1867, Glaister arranged to lease Crown land on the west shore of the Maribyrnong River at Footscray, between Napier and Parker streets (Figure 3).[56] After importing and adapting recently developed stone sawing technology capable of mechanically cutting hard bluestone, Glaister & Co. set up a stone sawing works and began sawing bluestone for paving and other purposes.[57] The bluestone was initially sourced from Glaister’s own quarries at Maidstone, and by September 1868 the cooperative was requesting supplies of bluestone from Malmsbury, Kyneton and Carlsruhe.[58] Within days, the Kyneton Guardian was reporting that the supply of bluestone for paving could not keep up with the demand.[59]

Figure 3: Location of Footscray stone cutting works, corner of Napier and Morland streets and adjoining the Maribyrnong River, Allotments B and C of Section 11A. PROV, VPRS16171/P0001/2 Cut-Paw-Paw Parish, Imperial Measure C2478-5.pdf (Footscray Township), 1906.

The works provided flagging for colonial and local government contracts, and Glaister & Co. began paving Victoria with their new products, gradually taming the mud and water that Melbourne’s residents perpetually endured.[60] Among their earliest instalments were the terrace of the Treasury buildings in 1867, two commercial Melbourne buildings in 1869, and paving for Emerald Hill, Melbourne, Prahran and Richmond councils between 1868 and 1871.[61] Imported and locally produced handmade flagging was now being replaced by a local product made by local workers at two-thirds of the price of the imports.[62] There were some 60 saws operating, capable of producing 500 feet of paving a day.[63] The sawing works alone employed 18 people, exclusive of the quarrying, freighting and laying of the stone.[64] An attempt in 1869 by Glaister to secure a lease of some adjoining Crown land for dwellings for workers and management was, however, unsuccessful.[65]

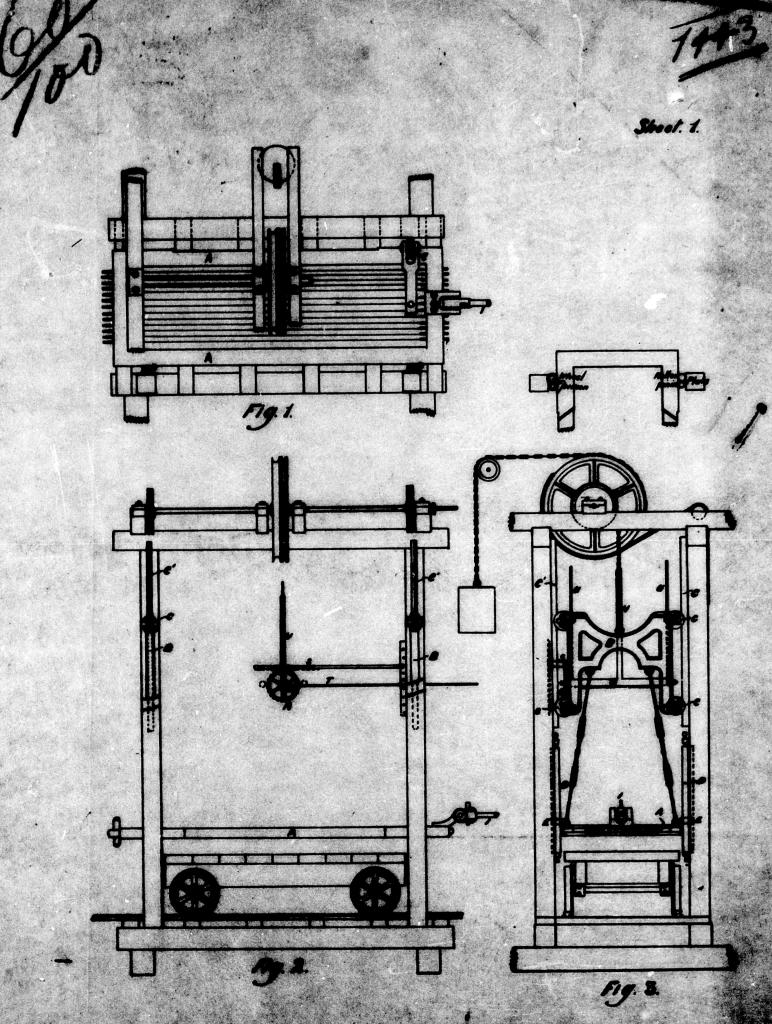

Eventually, a public company, the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Co., was formed and registered in August 1868 for the purposes of buying and operating the cooperative’s stone works. Among the seven original shareholders were Thomas Gamon, Leonard Carr, Thomas Glaister, Thomas Pearson and Isaac Ramsden, all former members of Glaister & Co., with Glaister appointed manager.[66] Glaister also registered two patents for his machinery designs, effectively giving the company a monopoly in cutting bluestone.[67] There is also evidence that the company repeated Glaister & Co.’s model of vertical integration to exclude capitalists by acquiring or managing local quarries to guarantee a supply of stone.[68]

The basic concept of the bluestone sawing works was similar to bread slicing, but cut at a much slower rate, taking hours or days rather than seconds. The metal blades were smooth edged, with several set parallel in frames that reciprocated by the action of a steam-driven crank on the upper surface of the stone block (Figure 4). It was the interaction of sand or quartz gravel, added from above, and the moving blades that cut through the stone. A constant supply of water washed away the pulverised sand and stone.[69] Adjusting the distance between the blades permitted the manufacturing of ‘thin’ flagging and gravestones, and ‘thick’ kerbs, sills and lintels.

Figure 4: Part of Glaister’s second stone sawing patent from 1870. State Library Victoria, Victorian Patent Number 1443 of 1870 – Thomas Glaister (Contractor) Footscray, Victoria.

As active and experienced masons, it is highly likely that the shareholders had heard of the reputation of the bluestone from Malmsbury, which was used extensively in the construction of the Woodend to Chewton portions of the Bendigo railway, through favourable press reports.[70] Malmsbury Bluestone is more porous, lighter in colour and less dense than Footscray stone, thus lending itself more readily to mechanical sawing.[71] By 1873, the bluestone sawn at Footscray was principally sourced from Malmsbury. In the space of four and a half years, between 1868 and mid-way through 1872, the quantity of stone being cut jumped from 7,500 cubic feet to 32,450 cubic feet, with some being exported to New Zealand.[72]

Realising that they were paying rail freight from Malmsbury to cart unprocessed stone, which always had some wastage attached, Glaister and the Malmsbury Council lobbied the Victorian Government for a reduction in the freight rates for bluestone.[73] While waiting to hear the outcome, Glaister’s next move was to apply for Crown land on the banks of the Campaspe River at Kyneton in 1870 on which he planned to establish another stone cutting works to process Carlsruhe Bluestone.[74] By being close to the railway station and the source quarries, the sawn material could be shipped up or down the line as required, thus expanding the northern markets for stone. However, there is no evidence that the Kyneton works went ahead.

Glaister & Co. assigned their interest in the Crown land leased at Footscray for stone sawing to the new company to permit them to purchase it from the Crown in February 1870.[75] The following year, the company also began leasing a further 2 acres of Crown land adjoining their existing site and in May 1878 this too was purchased from the Crown.[76]

From here Gamon and Glaister parted company. Thomas Gamon remained active in the stone sawing business until at least 1880.[77] However, Glaister departed for England in May 1871, on his own, to undertake further research to perfect stone sawing machinery.[78] The fact that he could afford to stop work and undertake this travel is probably one measure of the success of the eight-hour day and his business model. His movements from his departure in May 1871 until November 1881 are unknown, including the timing of his return to the Australian colonies. His wife Margaret died in England in 1887, apparently estranged from her husband. Regarding their two surviving sons, William appears to have departed Victoria after 1871 and was alive in 1888, and Joseph moved to South Australia between 1874 and 1892. In November 1881, Glaister reappeared in Melbourne, attending a meeting to form the Victorian Clerks of Works Association. Two months later, he was the clerk of works for the new Colonial Bank building in Collins Street.[79] Coincidentally, this now-demolished building had a carved ornate doorway of Malmsbury Bluestone, a portion of which now fronts the underground carpark entrance at the University of Melbourne.[80]

In the meantime, the Footscray company was voluntarily wound up and its assets transferred to the members in 1872, who then proceeded to carry on the business under the same name.[81] Gamon was a shareholder of the new company but not Glaister. Once more aiming to ensure control of the supply of bluestone, the new company purchased quarry land at Malmsbury in 1872.[82] This company lasted until 1882. Five years later, the original land in Footscray was used to establish yet another company, the Footscray and Malmsbury Stone-Cutting and Quarrying Company.[83] This new company purchased some of the Malmsbury quarry land in 1889, as well as newer quarries to the north-east of the town. Changing its name to the Footscray and Malmsbury Stone Company in 1913, the company appears to have been wound up sometime between 1915 and the early 1920s.[84]

From 1873, the demand for Malmsbury Bluestone in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand continued to grow. The uses to which it was put ranged from flagstones (paving), kerbs, lintels, steps, foundation stones, memorials, graves, columns, and base courses of large private, government and commercial buildings. It was installed in major centres like Melbourne, Adelaide, Fremantle, Perth, Hobart, Launceston, Sydney, Auckland and Wellington, in addition to many urban and rural settings between these cities. This includes the Auckland (Figure 5) and Wellington town halls, the interior walls and columns of St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne (Figure 6), the basecourse and steps of Customs House in Launceston, and flagging and kerbs in Sydney. Glaister and the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company actively lobbied the Sydney City Council to use its products.[85]

Figure 5: Auckland Town Hall, New Zealand, showing the Malmsbury Bluestone basecourse and ornate doorway. Photograph Susan Walter, 2016.

Figure 6: St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne, showing the Malmsbury Bluestone in the banded walls and columns. Photograph John Walter, 2023.

To date, the author has recorded over 500 reported sites at which Malmsbury Bluestone was used. Many of these sites, some of which are on national, state or local heritage registers, survive. Some of the citations for the more notable structures record the presence of the stone, others do not.[86] Many more sites of usage may remain unknown, due in part to the diversity of Malmsbury Bluestone products, lack of newspaper reporting (or digitisation of them) of those uses, and the absence or inaccessibility of private archives that record its purchase. One possible non-destructive way to correctly identify stone is the use of a portable XRF (X-ray fluorescence), but the cost and use of this equipment is prohibitive to the average historian or stone enthusiast.[87]

Life after bluestone

After returning to Australia, Glaister spent some time in the 1880s trying to develop the quarrying and sawing of marble in Kapunda, South Australia.[88] Returning to Victoria in 1886, and remarrying in 1888, he, like many others, was a victim of the land crash of the 1890s.[89] Ageing and out of work, Glaister and his second wife selected land near Diamond Creek on which they planned to grow an orchard and wattle trees to supply bark for tanneries in 1892.[90] However, a bush fire in 1893 wiped out the property. This forced Glaister to not only repeatedly beg the government for time to pay his rent, but also to borrow money to buy cows and plant strawberries in the hope of some quick returns on his labours. Illness and the lack of frequent work prevented Glaister from paying his rent until 1900, just four years before his death.[91] Awarded an age pension in 1902, Glaister died in relative obscurity in 1904 aged 79, his cause of death a fractured femur.[92] Thomas Gamon outlived him by four years. Although described as a ‘gentleman’ on his probate records, Gamon was not a wealthy man. Indeed, he had barely more assets to his name than ‘orchardist’ Glaister.[93]

Glaister & Co.’s contribution to Victoria’s building development, stone industry, labour history, worker cooperatives and industrial innovation has largely been forgotten. Many of the company’s architectural legacies remain today, their significance illustrated by the legal protection provided by the Victorian Heritage Register. However, little of the recorded history or surviving heritage highlights the foresight, involvement and working-class ethic of the talented and innovative men behind Glaister & Co. who sought to share the benefits of their education, skills and labours to improve the lives of their fellow men.[94] Without their investment in their trade, and their industrial processing of Victoria’s iconic building stone, the nomination of Malmsbury Bluestone as a UNESCO GHSR is unlikely to have succeeded. The GHSR nomination process required a summary of the history of the use of the stone—including its social history and the cultural impacts of its use—details of which are often scarce in citations of our built heritage, despite bluestone being an iconic feature of Melbourne and Victoria. This article demonstrates that the architectural and cultural use of bluestone in Victoria and beyond is inherently intertwined with the social and labour history of stonemasons. Stone, as Edensor demonstrates in loving detail, is used to commemorate our past, create enduring cultural places, remind us of the forgotten, and provide a sensory connection with people, places and actions.[95] Even though we currently struggle with politically or morally contentious statues, the stone of which they are made perpetually shows evidence of mankind’s ancient skills in manipulating inert materials.

Capitalists in disguise?

In asking if Glaister and Gamon were really capitalists, context is provided by the eight-hour day and worker cooperatives. Hughes argued that the cooperative movement in Australia developed in isolation from the labour movement, yet Glaister & Co.’s cooperative model apparently developed because of the movement. With the eight-hour day established and delivering direct benefits for their fellow workers, the masons were able to take on the capitalist employers in other ways.[96] None of Hughes’s main phases of the development of cooperatives stated earlier adequately explain Glaister & Co’s cooperative model. They were a small group and, while they received mutual benefits by being their own masters and pooling their skills and resources, the flow-on effect to others in their trade was probably indirect.

Drawing on Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic’s research, Glaister and Gamon’s cooperative can be adequately described as a workers cooperative, not an investor owned business (IOB), which focuses on providing ‘a good money return to investors’.[97] Certainly, the Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company was an IOB (despite several of its shareholders being members of the second cooperative), as was the subsequent entity, the Footscray and Malmsbury Stone-Cutting and Quarrying Company (which entirely moved away from the democratic model to the IOB model). However, the fact remains that the original success of the cooperative made these other businesses possible.

With no need to strike, the cooperative members did not need to raise funds to support striking workers, a function of later consumer cooperatives, such as in Wonthaggi.[98] In a world where Victorian workers ‘found out that their only real friend, the only one they could thoroughly depend on, was the working man himself’, Glaister & Co. took matters into their own hands to deliver income, reputation and a future for their members.[99] The fact that neither man was especially wealthy at the time of his death suggests that they either failed at capitalism, perhaps due to personal, moral and labour ethics, or that they never attempted to engage in it in the first place; either way, the lines between labour and capitalism appear blurred. Both Glaister and Gamon worked to further their industry, not to exploit it or their comrades; however, for this, they needed economic capital. At the same time, they invested and traded in cultural and social capital, the personal costs of which are probably immeasurable.

Arguably, the original success of the stone sawing works, before it was a public company and needed to provide a financial dividend, provides the definitive answer to the question of whether Glaister and Gamon were capitalists: those who seek to tame stone rely on some capital, but it also takes skill, ethics and compassion, which capitalists cannot always buy. An interpretation of the history of bluestone in Victoria, and its cultural heritage significance, should be seen in this light. In the same way that Melbourne is a composite of banks, churches, post offices, shops, docks, prisons and streets, each of these constructions is also a composite of the materials with which they were built and the people who built them. While we still need to consider their architectural importance, glossing over or totally ignoring those who built them, their skills in handling materials and their labour struggles, is akin to placing heritage protection on a roof and forgetting the walls that support it. The growing efforts of IUGS to designate GHSRs from a geoheritage perspective will ultimately provide a ‘quarry of ideas’ that will make this exclusion harder to justify.

Endnotes

[1] Tom Griffiths, The art of time travel: historians and their craft, Black Inc., Carlton, 2016.

[2] International Union of Geological Sciences – International Commission on Geoheritage, ‘Malmsbury Bluestone’, Designations, <https://iugs-geoheritage.org/geoheritage_stones/malmsbury-bluestone/>, accessed October 2024.

[3] Robyn Annear, A city lost & found: Whelan the wrecker’s Melbourne, Black Inc, Collingwood, 2014.

[4] Maie Casey (ed), Early Melbourne architecture 1840 to 1888, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1963.

[5] Alan H Spry, Building stone in Melbourne: a history of stone use in Melbourne particularly in the nineteenth century, Report for the Australian Heritage Commission and The Victorian Historic Buildings Council, 1988, (Table 17) 99–102.

[6] A search in March 2025 of Trove for ‘bluestone’ in the Age and Argus alone, for example, produces over 64,000 results.

[7] Tim Edensor, Stone: stories of urban materiality, Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore, 2020, pp. v, 171.

[8] JG Knight, A treatise on Australian building stones, read at a meeting of the Victorian Institute of Architects, London, Yates and Alexander, 1864.

[9] Spry, Building stone in Melbourne.

[10] Miles Lewis, ‘3.06 stones’, Australian building: a cultural investigation, 2013, available at <https://www.mileslewis.net/australian-building>, accessed 6 May 2013.

[11] PROV, VPRS 947/P0000, Unit 1, Inward Overseas Passenger Lists, November 1852, Chalmers, p. 3.

[12] Susan Walter, ‘Malmsbury Bluestone and quarries: finding holes in history and heritage’, PhD thesis, Federation University Australia, 2019, pp. 199–208.

[13] WE Murphy, History of the eight hours' movement, Spectator Publishing Company, Melbourne, 1896, pp. 61, 80a.

[14] Ibid., 61, 80a.

[15] ‘Eight hours jubilee’, Age (Melbourne), 21 April 1906, p. 14; Noel Butlin Archives, Australian National University, Operative Stone Masons Society of Australian, Victoria Branch Deposit, Series E117, Item 1–2, Minutes of Melbourne Lodge of Operative Masons, 26 January 1857; ‘The masons’, Argus (Melbourne), 3 October 1857, p. 6.

[16] ‘The convention’, Age, 23 November 1857, p. 5; ‘The stonemasons and the convention’, Argus, 14 December 1857, p. 6; ‘Political organization of labor’, Argus, 23 March 1859, p. 5.

[17] ‘Monument of the late Mr Galloway’, Williamstown Chronicle, 3 July 1869, p. 3.

[18] Murphy, History of the eight hours' movement, p. 61; ‘Monument of the late Mr Galloway’.

[19] John Maxwell, ‘Cornish, William Crocker (1815–1859)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, <https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cornish-william-crocker-3263/text4941>, published first in hardcopy 1969, accessed online 9 March 2025; ‘The new houses of parliament’, Argus, 17 April 1856, p. 6; ‘The eight hours struggle’, Age, 22 April 1856, p. 3.

[20] ‘Labor in Australia’, Argus, 4 November 1858, p. 1; ‘Labor and wages in Victoria’, Argus, 8 November 1858, p. 5; ‘The railway contractors’, Argus, 9 November 1858, p. 5; TA Coghlan, Labour and industry in Australia, Volume 2, Oxford University Press, London, 1918, p. 737

[21] Jeff Rich, ‘The traditions and significance of the eight hour day for building unionists in Victoria 1856–90’, in Julie Kimber and Peter Love (eds), The time of their lives: the eight hour day and working life, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Melbourne, 2007, p. 38.

[22] ‘Police’, Geelong Advertiser, 19 January 1859, p. 3; ‘Organised Melbourne trades meeting’, Geelong Advertiser, 19 January 1859, p. 2; ‘Police’, Geelong Advertiser, 3 February 1859, p. 3.

[23] ‘The Masters and Servants Act – the masons’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth), 1 February 1859, p. 3; Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle (Melbourne), 12 February 1859, p. 47. This Act stems from the Act for the Better Regulation of Servants Laborers and Work People 1828 (No. 9) (NSW) and thus was continued in the colony of Port Phillip in various amended and consolidated forms. The Victorian Legislative Council voted to continue it in 1852. This was followed by Masters and Servants Statute 1864 (No. 198) (Vic.) and An Act to Amend And Consolidate the Laws between Masters and Servants in New South Wales (No. 27) (NSW). While the Geelong Advertiser used the term ‘mechanic’, the Act uses ‘artificer splitter fencer sheep shearer or person engaged in mowing reaping or getting in hay or corn or in sheep washing or other laborer’.

[24] ‘Railway intelligence’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 19 February 1859, p. 56; ‘Police’, Geelong Advertiser, 16 February 1859, p. 3.

[25] ‘Political organization of labor’.

[26] ‘The associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 26 March 1859, p. 92; ‘Associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 9 April 1859, pp. 103, 108; ‘Law and judicial notices’, Age, 25 April 1863, p. 7.

[27] Although Glaister and Co. are not named in these works, the timing fits. They were the only such group to have a contract to build part of Pentridge from 1859 and they had 40–50 members. It was also probably the novelty of the group that attracted media attention/criticism.

[28] Coghlan, Labour and industry in Australia, 1036.

[29] Greg Patmore, Nikola Balnave and Olivera Marjanovic, ‘Worker co-operatives in Australia 1827–2024’, Journal of Industrial Relations, 2024, p. 9, <https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856241287898>.

[30] The author did not find any evidence of these two cooperatives during research for this paper.

[31] Vern Hughes, ‘Co-operatives and the labour movement’, Recorder (newsletter of the Melbourne Branch of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History), August 1999, p. 2.

[32] Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic, ‘Worker co-operatives in Australia’, p. 2.

[33] Hughes, ‘Co-operatives and the labour movement’, pp. 2–3.

[34] Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic, ‘Worker co-operatives in Australia’.

[35] Ibid., pp. 3–4, Table 1 and Figure 2.

[36] ‘Contracts accepted’, Victoria Government Gazette (VGG), 1 April 1859, p. 632; ‘The associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 26 March 1859, p. 92.

[37] Walter, ‘Malmsbury Bluestone and quarries’, pp. 202–206. The Chinese Court is probably now called the Num Pon Soon Society Building at 200–202 Little Bourke Street, see: ‘Public Works’, Age, 25 March 1861, p. 6.

[38] ‘Crown land sale’, Argus, 31 August 1859, p. 1; ‘Thomas Glaister’, Registrar General’s Office (RGO), General Law Archives, Vendors Index, Second Series, Book 32, p. 43. The land in question is in section 64 parish of Jika Jika (North Melbourne).

[39] ‘Miscellanea’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 4 June 1859, p. 171; ‘Miscellanea’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 18 June 1859, p. 188; ‘Contracts accepted’, VGG, 15 July 1859, p. 1481.

[40] ‘Contractors and co-operative associations’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 28 January 1860, p. 21.

[41] ‘Reduction on mason’s wages’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 11 February 1860, p. 33; ‘Correspondence’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 18 February 1860, p. 44.

[42] Noel Butlin Archives, Series E117, Item 2-2, Minutes of Central Committee meetings, Friendly Society of United Operative Masons, minutes, 24 December 1858 to 9 June 1859, his name no longer appears as attending meetings from this last date. See also ‘Mr Harker on sub-contracting’, Age, 12 August 1859, p. 4.

[43] ‘Associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 9 April 1859, p. 103; ‘Correspondence’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 30 April 1859, p. 133; ‘Associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 7 May 1859, p. 140; ‘Associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 14 May 1859, p. 147; ‘Mr WB Smith and the masons’, Argus, 21 December 1859, p. 6.

[44] ‘The associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 26 March 1859, p. 92; ‘The masons’, Argus, 3 October 1857, p. 6; ‘Contractors v. laborers’, Kyneton Observer, 12 June 1858, p. 2; ‘Associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 9 April 1859, p. 108; ‘Associated masons’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 14 May 1859, p. 147; ‘Mr WB Smith and the masons’; ‘The masons and the strike’, Argus, 23 December 1859, p. 5.

[45] ‘The news of the day’, Age, 4 October 1860, p. 5; ‘A visit to the new General Post-Office’, Argus, 3 January 1861, p. 5; ‘Merchandise’, Argus, 2 December 1864, p. 8.

[46] ‘Shipping’, Mercury (Hobart), 1 November 1862, p. 4; Tasmanian Birth Registrations 669/33 of 1863 for Alice Esther GAMAN (sic GAMON) and 1578/33 of 1865 for Thomas Francis GANNON (sic GAMON); ‘The governor’, Mercury, 21 April 1865, p. 3 (erroneously recorded as Gamau); PROV, VPRS 944/P0000, Inwards Passenger Lists (Australian Ports), December 1865, Harriett Nathan, arrived from Hobart.

[47] ‘Houses and land for sale’, Argus, 29 April 1865, p. 8; ‘Tradesmen’, Argus, 1 August 1865, p. 1; ‘The graving dock’, Argus, 18 August 1865, p. 5; PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, 1860 Volume A, p. 270, Item 4074, 15 July 1860.

[48] Victoria, Statistics of the colony of Victoria for the year 1860 compiled from official records in the Registrar-General's Office, Victoria, 1861, pp. 148 and 192 show imports of building materials and stone into Victoria from interstate and overseas, available at <https://pov.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_GB/parl_paper/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:46679/one>, accessed 22 April 2024.

[49] ‘The convention and the masons’, Age, 3 December 1857, p. 6.

[50] ‘The news of the day’, Age, 6 April 1863, p. 5, ‘Law and judicial notices’, Age, 25 April 1863, p. 7.

[51] RGO, Land Memorials, Book 174, Memorial 916 Assignment from Glaister, Carr, Gamon & Moore to Enoch Chambers, 1867, for land in parish of Cut Paw Paw; ‘To our readers’, Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers (Melbourne), 3 March 1868, p. 2; Kyneton Observer, 1 March 1859, p. 1.

[52] RGO, Land Memorials, Book 127 Memorial 366 (1863), Book 128 Memorial 780 (ca1864), Book 173 Memorial 358 (ca 1867), Book 190 Memorial 419 (1869) relating to conveyance and mortgages of land in Section 64, Allotments 8 and 9, parish of Jika Jika.

[53] ‘Contracts accepted’, VGG, 27 September 1864, p. 2131; ‘Contracts accepted’, VGG, 29 November 1864, p. 2670; ‘The graving dock’.

[54] Rich, ‘The traditions and significance of the eight hour day’, p. 28.

[55] ‘The masons’, Argus, 3 October 1857, p. 6.

[56] ‘Melbourne’, Geelong Advertiser, 24 July 1867, p. 3; PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, Unit 12, 1867 Volume P, p. 263, Item 5376, 7 May 1867, the register summary is ‘Thomas Glaister & Co apply under the 50th clause of Land Act for a lease of 1ac of land at the junction of Napier street with Saltwater River at Footscray’; PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, Unit 12, 1867 Volume O, p. 542, Item 10256, 20 August 1867 ‘Woolcott & Turner, per Glaister & Co. refer to Glaister’s application for lease of land at Footscray for sawing bluestone etc and request that marble, granite & freestone be included’.

[57] ‘Sawing blue stone’, Williamstown Chronicle, 5 October 1867, p. 6.

[58] Australasian (Melbourne), 12 October 1867, p. 18; ‘Building materials’, Argus, 2 September 1868, p. 8; ‘Wanted’, Kyneton Guardian, 5 September 1868, p. 3.

[59] Kyneton Guardian, 12 September 1868, p. 3.

[60] ‘Wood pavement’, Argus, 6 April 1857, p. 4

[61] Australasian, 12 October 1867, p. 18; ‘The news of the day’, Age, 23 January 1869; 2; ‘Bluestone for foot pavement’, Telegraph (St Kilda, Prahran & South Yarra), 15 July 1871, p. 7; ‘An undeveloped industry’, Kyneton Guardian, 28 August 1869, p. 2.

[62] Australasian, 12 October 1867, p. 18.

[63] ‘Melbourne’, Geelong Advertiser, 10 September 1868, p. 3.

[64] Kyneton Guardian, 7 October 1868, p. 2.

[65] PROV, VPRS 44/P0000, Unit 198, Item 57, File 69/V 22797, 21 October 1869.

[66] PROV, VPRS 932/P0000, Unit 11, File 133 Footscray Steam Stone-Cutting Company; ‘Public companies’, Argus, 19 June 1868, p. 2; ‘Private advertisements’, VGG, 1 September 1868, p. 1642.

[67] State Library Victoria (SLV), Victorian Patent Number 1298 of 1869 – Thomas Glaister (Contractor) Footscray, Victoria; Victorian Patent Number 1443 of 1870 – Thomas Glaister (Contractor) Footscray, Victoria, both accessed via Victorian Patents [Microform], Melbourne, 1980.

[68] Kyneton Guardian, 14 May 1870, p. 2; ‘Kynetonshire Council’, Kyneton Guardian, 15 February 1871, p. 3; PROV, VPRS 24/P0000, Unit 286, Item 1873/119 Inquest Isaac Stephenson 4 February 1873.

[69] Argus, 6 October 1868, p. 5; SLV, Victorian Patent Number 1298 of 1869, and Victorian Patent Number 1443 of 1870.

[70] ‘Telegraphic despatch’, Argus, 22 March 1861, p. 5; ‘Miscellanea’, Australian Builder and Railway Chronicle, 30 July 1859, p. 235.

[71] R Brough Smyth, Mining and mineral statistics with notes on the rock formations of Victoria, Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, Melbourne, 1873, p. 36.

[72] Ibid, pp. 36–37; Argus, 25 October 1873, p. 5

[73] ‘An undeveloped industry’; Argus, 16 October 1869, p. 5; Kyneton Guardian, 16 October 1869, p. 2.

[74] PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, Unit 12, 1870 Volume ‘&’, p. 132, Item 22999, 11 October 1870; VPRS 16306/P0001, Put-Away Plan L120F: Townships of Kyneton and Lauriston – Survey, 1875; Kyneton Guardian, 18 January 1871, pp. 2, 3; ‘Kynetonshire Council’.

[75] PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, 1870 Volume Z, p. 30, Item 1400, 18 January 1870; PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, 1870 Volume Y, p. 212, Item 7507, 23 March 1870; ‘Sale of Crown lands in fee-simple’, VGG, 25 February 1870, p. 383.

[76] PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, 1871 Volume B, p. 349, Item 12091, 19 July 1871; PROV, VPRS 70/P0001, 1873 Volume J, p. 55, Item 2337, 6 February 1873; ‘Sales of Crown lands in fee-simple’, VGG, 12 April 1878, p. 819; PROV, VPRS16171/P0001/2 Cut-Paw-Paw Parish, Imperial Measure C2478-5.pdf (Footscray Township), 1906.

[77] PROV, VPRS 932/P0000, Unit 30, File 482 Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company.

[78] ‘The news of the day’, Age, 3 May 1871, p. 2; ‘The town’, Leader (Melbourne), 6 May 1871, p. 12; PROV, VPRS 948/P0001, Outward Passengers to Interstate, U.K. and Foreign Ports, Jan–June 1871, Asia, Departed May 1871, p. 3, (recorded on digital index as Plaister).

[79] PROV, VPRS 515/P0001, Unit 13, p. 402, Prisoner Record 9092, Joseph Glaister (son of Thomas, the record says his father is in England); ‘Meetings’, Australasian, 19 November 1881, pp. 21–22; ‘The new Colonial Bank building’, Argus, 11 January 1882, p. 6.

[80] Annear, A city lost & found, pp. 83–87.

[81] ‘The Footscray Steam Stone-Cutting Company Limited (in liquidation)’, VGG, 1 March 1872, p. 486; PROV, VPRS 932/P0000, Unit 30, File 482 Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company.

[82] PROV, VPRS 460/P0002, 65675 Application for Certificate of Title for Portion 26 Parish of Edgecombe; ‘Tenders’, Argus, 15 March 1879, p. 10.

[83] PROV, VPRS 932/P0000, Unit 66, File 1130 Footscray & Malmsbury Stone Cutting & Quarrying Company; Walter, ‘Malmsbury Bluestone and quarries’, pp. 102–104, 125–129, 136–137.

[84] PROV, VPRS 932/P0000, Unit 66, Item 1130; ‘Private advertisements’, VGG, 28 July 1915, 2789; Victorian Certificate of Title, Volume 1933, Folio 386499, 1 August 1921.

[85] City of Sydney Archives, Letter, Thomas Glaister, manager, Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company, sending council a sample (10/11/1868 – 21/11/1868), [A-00299027]; Letter, Thomas Glaister, manager, Footscray Steam Stone Cutting Company, stating prices for sawn (30/11/1868 – 01/06/1869), [A-00299076]; Letter, John Woolcott (solicitor of 5 Collins St East Melbourne) for Footscray Steam Stone Cutting (10/12/1873 – 04/02/1874), [A-00283755].

[86] Walter, ‘Malmsbury Bluestone and quarries’, pp. 76–77, 80–82, 90–97, 112–116, 130, 385–392; Susan M Walter, ‘Victorian bluestone: a proposed global heritage stone province from Australia’, in JT Hannibal, S Kramer and BJ Cooper, Global heritage stone: worldwide examples of heritage stones, Geological Society, London, 2020, pp. 7–31.

[87] Michelle Richards, ‘Realising the potential of portable XRF for the geochemical classification of volcanic rock types’, Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 105, 2019, pp. 31–45. The equipment alone costs approximately A$30,000.

[88] South Australian Weekly Chronicle (Adelaide), 22 July 1882, p. 21; National Archives Australia, A13128, 347, Specification for registration of patent by Thomas Glaister titled – Improvements in machinery for sawing stone; ‘The parliament buildings contract’, South Australian Weekly Chronicle, 12 September 1885, p. 12.

[89] ‘Applications for patents for inventions’, VGG, 7 May 1886, p. 1171; Victorian Marriage Certificate, Registration Number 1896 of 1888 Thomas Glaister.

[90] PROV, VPRS 5357/P0, Unit 4136, File 18404/47.98.

[91] ‘Licensees in arrears under section 65 of the Land Act 1890’, VGG, 21 February 1895, p. 736; ‘Licensees in arrears under section 65 of the Land Act 1890’, VGG, 6 April 1898, p. 1265; ‘Renewal of licences approved’, VGG, 14 September 1900, p. 3526.

[92] ‘Old age pensions’, Evelyn Observer, and South and East Bourke Record, 7 March 1902, p. 2; Victorian Death Certificate, Registration Number 2294 of 1904 Thomas Glaister; ‘Deaths’, Weekly Times (Melbourne), 12 March 1904, p. 32.

[93] ‘Deaths’, Australasian, 18 January 1908; PROV, VPRS 28/P0000, VPRS 28/P0002, VPRS 7591/P0002, file 105/757, Probate and Will of Thomas Gamon, gent of Hawthorn died 14 January 1908; PROV, VPRS 28/P0000, VPRS 28/P0002, VPRS 7591/P0002, file 95/834, Probate and Will of Thomas Glaister, orchardist of Diamond Creek died 1 March 1904.

[94] Ararat Gaol, Melbourne GPO, the Alfred Graving Dock and parts of Pentridge are all listed on the Victorian Heritage Register, as is the Nun Pon Soon Society Building. The Victorian Heritage Database Reports for the Melbourne GPO, Ararat Gaol, Num Pon Soon building and Pentridge Prison, for example, make no mention of who the builders were. The report for Alfred Graving Dock records Glaister & Co. but with no context. See: Heritage Council Victoria, Victorian Heritage Database, Victorian Heritage Register Sites H1067 (Ararat Gaol), H0903 (General Post Office), H0697 (Alfred Graving Dock), H1551 (HM Prison Pentridge) and H0485 (Num Pon Soon Building), available at <https://www.heritage.vic.gov.au/heritage-listings/is-my-place-heritage-listed>, accessed 25 May 2024.

[95] Edensor, Stone: stories of urban materiality, pp. 171–216.

[96] Hughes, ‘Co-operatives and the labour movement’, p. 2.

[97] Patmore, Balnave and Marjanovic, ‘Worker co-operatives in Australia’, p. 2.

[98] Nikola Balnave and Greg Patmore, ‘The politics of consumption and co-operation: an overview’, Labour History, no. 91, 2006, p. 4.

[99] ‘Inauguration of the Trades’ Hall’, Age, 25 May 1859, p. 5.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples