Last updated:

‘Turbulent tales within the archives’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 22, 2025. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Chris Carpenter.

Exploring the Carpenter family’s saga via Public Record Office Victoria reveals a vivid tapestry beyond basic genealogical sources such as birth, marriage and death records. Richard Snr and Maria Carpenter, immigrants from England, anchor this narrative, with their descendants’ lives unfolding against the backdrop of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Victoria. The story focuses on three of their children, Richard Jnr, William and Elizabeth. Their lives were documented in meticulous archival records, reflecting a complex history of mental health issues and interactions with numerous institutions during their lifetimes. Through the lens of the state archives—court records, ward registers, asylum reports, shipping records, probate records, rate records and gazettes—the Carpenter family is transformed into a vibrant narrative of migration, survival, adversity, resilience and controversy in colonial Australia.

Disclaimer: This article includes language and descriptions that reflect the attitudes and terminology of the historical period it discusses. Some terms, such as ‘lunatic’ and ‘maniacal’, as well as other expressions, were sourced from contemporary documents and may be considered offensive or distressing by today’s standards. The inclusion of these terms is intended solely to provide an accurate representation of the historical context and does not reflect the views or beliefs of the author. Reader discretion is advised.

Introduction

The story of the Carpenter family, English immigrants to Australia, is more than just a historical account—it is a deeply personal exploration of my own ancestry. Richard Snr and Maria Carpenter, my third great-grandparents, arrived in Victoria in the mid-nineteenth century. Their descendants’ lives offer a window into the challenges and transformations of colonial Victoria. My decades-long passion for family history led me to uncover their lives, revealing a story of resilience, hardship and survival.

Traditional genealogical sources such as birth, marriage and death records provide a foundation, but the true depth of this story emerges from state archives. This story exists today because the family appeared in a variety of official records—court records, ward registers, shipping records, probate records, rate records and gazettes, among others—all documenting their lives in remarkable detail. This article focuses on three of Richard Snr and Maria’s children—Richard Jnr, William and Elizabeth—who were my second great-granduncles and second great-grandaunt. Each of them left a compelling legacy.

Richard Jnr led a turbulent life under multiple aliases, marked by five marriages, numerous fraud and desertion charges, and fathering at least 27 children. His story paints a striking portrait of personal reinvention and deception. William Carpenter’s life was overshadowed by mental health struggles, reportedly brought on by sunstroke. His repeated admissions to asylums, and eight documented escapes from institutions in Ararat, Ballarat and Kew, highlight his personal turmoil and the broader challenges faced by those with mental illness in colonial Victoria. Elizabeth Carpenter spent over 60 years institutionalised at the Ararat Asylum. Her story serves as a poignant reminder of the harsh realities of mental health care in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Victoria. Through the lives of these three siblings, this article explores themes of migration, crime, mental illness and institutionalisation, offering a personal yet historically significant reflection on a family navigating a rapidly changing country.

Journey to Australia

On 3 February 1849, the Western Times in Devon, England, published an article headlined ‘Emigration to Australia’, claiming that men who left England without a penny in their pockets were now well-established in positions of independence.[1] Soon afterwards, Mr G. H. Haydon, a former Australian resident, lectured in Exeter on emigration, describing Australia as a place with uncultivated land offering immediate employment to newcomers. He noted: ‘The moment an emigrant lands he finds employment, and often before he sets his foot on shore.’ Mr Haydon also spoke of a local resident from Kenton who was enjoying good fortune in Australia.[2]

Kenton, a small town about 15 kilometres south of Exeter, was home to Richard Snr and Maria Carpenter. As children, both had grown up in poor families, being apprenticed by the age of 10 under the United Kingdom’s Poor Relief Act 1601.[3] By the late 1840s, they were married with three children, and Richard Snr was working as a labourer.[4] The promise of a better life in Australia was tempting, especially after Richard Snr lost his mother[5] and brother[6] in 1841, and Maria lost her father in 1848.[7] By April 1849, they had made the decision to emigrate.

On 27 April 1849, the Medway set sail from London carrying 31-year-olds Richard Snr and Maria Carpenter, and their children Ellen (10), Richard Jnr (7) and William (5).[8] Like many passengers, the Carpenters could barely read and could not write. Unlike most on board, they did not carry a Bible.[9] They arrived at Point Henry in Geelong on 9 August 1849 after a voyage of just over 100 days (Figure 1). Although one adult and one child died during the journey, two births occurred, keeping the total number of passengers at 262.[10]

Figure 1: The Carpenter family’s journey to Australia is documented in assisted passenger lists. PROV, VPRS 14/P0 Register of Assisted Immigrants from the United Kingdom, Book No. 5A, p. 39.

Upon arrival, the family spent nine days in the Immigration Depot, from 20 to 28 August 1849, before Richard Snr and Maria were employed as farm labourers by Mr Waldie at Buninyong for six months, earning £28 per annum each.[11]

A growing family in Burrumbeet

By the late 1850s, the family had grown to nine members, with the births of Emily,[12] Henry,[13] Edward[14] and Elizabeth.[15] They settled in Burrumbeet, where they would remain for most of their lives.[16] However, the coming decades brought numerous challenges, including a young death, false identities, a record number of children, an escape artist, and lives marked by mental illness and institutionalisation.

Richard Jnr Carpenter: Five wives and 27 (or 28) children, mainly deserted and placed in state care

Disfunction in the Carpenter family became evident in the early 1860s. In May 1862, tragedy struck when Richard Snr and Maria’s eight-year-old son Henry died from diphtheria. He was buried two days later in the Learmonth Cemetery.[17] Richard Jnr (Figure 2) was the informant on his death certificate.

Figure 2: Richard Carpenter Jnr. Private Carpenter Family Collection.

Six months earlier, Richard Snr had published a notice in the Star stating that Richard Jnr, his 19-year-old son, was not authorised to contract debts or transact business on his behalf (Figure 3).[18] This was the beginning of Richard Jnr’s tumultuous life.

Figure 3: The early start to Richard Jnr’s life of deception is highlighted in this newspaper article. ‘Notice’, Star (Ballarat), 25 November 1861, p. 3, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66343720>.

Born on 5 January 1842 in Devon, England,[19] Richard Jnr married five times, fathered 27 children and led a life marked by fraud, deception, numerous aliases and the abandonment or early death of most of his children.

On 26 September 1865, Richard Jnr, aged 23, married 20-year-old Susan Downes at Fitzroy.[20] He listed his parents as Richard Snr Carpenter and Maria Dally, but falsely claimed his birthplace was Melbourne. Three weeks later, Richard Jnr was charged with obtaining a £25 cheque from James Valentine Taite (Figure 4).[21] This was the beginning of a series of criminal activities and multiple identities.

Figure 4: Richard Jnr Carpenter’s first appearance in Victoria Police Gazette, no. 42, 19 October 1865, p. 383.

Richard Jnr’s second marriage, on 9 September 1867, was to 24-year-old Elizabeth Neylan in Roma, Queensland.[22] Using the alias George Carpenter, he falsely claimed Melbourne as his birthplace again. They had five children: John,[23] Richard Joseph,[24] Thomas,[25] Mary Elizabeth[26] and Martin.[27] The eldest, John, only lived for a few days.[28] Richard Jnr continued his criminal activities, including stealing a horse in 1877.[29] He was charged in 1879 with deserting his four children,[30] aged between 10 and 4, who were found wandering in High Street, Echuca (Figure 5). The children were brought before the Echuca Police Court and committed to state care under the Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act 1864 (No.216) (NSW) (Figure 6).[31] The children’s mother, Elizabeth, would go on to live an impoverished life, being sentenced to six months imprisonment for vagrancy in 1896 at Nathalia Petty Sessions,[32] and later dying in tragic circumstances in 1900.[33]

Figure 5: Richard Jnr Carpenter in the Victoria Police Gazette, no. 38, 24 September 1879, p. 240.

Figure 6: Two of Richard’s Jnr’s children, Richard Joseph Carpenter and Thomas Carpenter, committed to state care. PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 8915 – 12311, Boys neglected – Register 12, p. 645.

Within a year and a half of deserting his children from his second marriage, 39-year-old Richard Jnr married his third wife, 19-year-old Catherine Elizabeth Sutton on 12 January 1881 at Seymour, using the alias William Ross, again incorrectly listing his parents and birthplace.[34] They would have eight children over the next 15 years: Charles Ross,[35] Edward,[36] Emily Annie,[37] Catherine Elizabeth,[38] Matilda Lavinia,[39] Ethel Dora,[40] Rebecca Ruth[41] and Edith Mae Lily.[42] They moved to Elmhurst, 200 kilometres west of Seymour, during the mid-1880s.

During the 1890s, Richard Jnr appeared more than a dozen times at the Court of Petty Session, mostly for claims of money for goods and services or nuisance-related matters.[43] In December 1897, history repeated itself when Richard Jnr deserted Catherine. This time it was believed he had gone to Western Australia.[44] Subsequently, five of his children appeared before the local court for being neglected and wandering the streets without any means of support. Emily Annie (12), Kate Elizabeth (10) (Figure 7), Matilda Lavinia (8), Ethel Laura (6) and Rebecca Ruth (4) appeared on 6 May 1898 and again on 3 June and 1 July, and the younger four were committed to state care.[45]

Figure 7: Kate Elizabeth Carpenter, one of Richard Jnr’s children, is committed to state care. PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 23240 – 23540, p. 170 (cropped).

On 25 August 1898, just a few weeks after four of Richard Jnr’s children from his third marriage were committed to state care, he married 18-year-old Anna Elizabeth Sorenson at Trentham, 100 kilometres east of his previous Elmhurst residence. Aged 56, he married under a new alias, Robert Sutton, and listed his mother as Elizabeth Nealan (his second wife’s name).[46] They had two children: Jane Lavinia[47] and Mary Rebecca.[48] In 1901, his daughter Jane[49] and wife Anna both died.[50] Anna’s cause of death was acute gastritis. Richard Jnr abandoned his two-month-old baby, Mary Rebecca, who was left in the care of Mrs Jane Saunderson.[51]

A few months later, in February 1902, 60-year-old Richard Jnr, once again using the alias Robert Sutton, married for the fifth time, this time in Ballarat to 20-year-old Mary Anne Moore.[52] They would have 12 children over the next 20 years: Thomas,[53] Maggie,[54] Annie,[55] Robert,[56] Ellen,[57] Vera Jane,[58] Elizabeth,[59] Mary Ann,[60] Ivy,[61] Richard Martin,[62] Hughie Joseph[63] and Maria Teresa.[64]

Less than a month after his fifth marriage, Richard Jnr was arrested by Bungaree police for deserting his infant child from his fourth marriage (Figure 8). Constable Anderson of Bungaree arrested him at Barkstead on a charge of child desertion, subsequently bringing him to the Ballarat Goal to await his court appearance.[65]

Figure 8: Richard Jnr Carpenter (aka Robert Sutton) in the Victoria Police Gazette, no. 7, 13 February 1902, p. 67.

In July 1902, Richard Jnr appeared before the court at Kyneton, charged with child desertion. However, due to a defect in the warrant—it had not been stamped—he was discharged.[66]

On 23 January 1911, Richard Jnr and Mary Anne’s five eldest children—Thomas (Figure 9), Maggie, Annie, Robert and Ellen—were committed to state care for being neglected. Frequently sent out by their parents to beg, they were said to be living in a filthy, starving condition, when rescued by the police. Poverty stricken, Richard Jnr was described as an aged pensioner and Mary Anne as a ‘useless lazy woman’. The family lived in a dilapidated dwelling, the only piece of furniture being a bed.[67]

Figure 9: Thomas Carpenter, Richard Jnr’s son, committed to state care. PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 34622–34920, p. 185.

Shortly after their eldest five children were committed to state care, Richard Jnr and Mary Anne’s youngest child, Elizabeth, died in March 1911,[68] leaving only Vera Jane in their care at this time. A few weeks later, on 22 April 1911, Richard Jnr appeared before the Court of Petty Sessions at Ballarat. His wife Mary Anne charged him with leaving her without adequate means of support, but the accusation was withdrawn.[69] In the following years, a further two daughters, Mary Ann[70] and Ivy,[71] died within weeks of birth. Richard Jnr and Mary Anne went on to have three more children: Richard, Hughie and Maria.

In 1921, Ballarat East Police painted a dismal picture of Richard Jnr’s living conditions, stating that he, an aged pensioner, lived in poor circumstances. The police reported that the house, which he shared with a woman believed to be his wife, was unclean. The woman, also a pensioner, was described as having a weak intellect. It was noted that a well-known prostitute was often entertained in the home and, as such, it was recommended that the children not be returned under any circumstances.[72]

After the death of his brother William in 1922,[73] Richard Jnr moved to Flint Hill, Ararat, where he lived on his brother’s property overlooking the Ararat Asylum. He gained some notoriety in 1925 when, aged 83, he appeared in the Ararat Police Court. Newspapers across Australia reported on the case under headlines such as ‘Father of 28’ and ‘Record family’—though only 27 children have been confirmed.[74]

Richard Jnr’s wife Mary Anne passed away on 26 November 1930.[75] One of his final acts was to commit his youngest child, Maria, to state care on 13 May 1931.[76] He died 18 months later, on 18 November 1932, alone in his hut on Picnic Road. His cause of death was senile debility;[77] he left no will,[78] having married five wives and fathered at least 27 children, more than half of whom he had abandoned.

Richard Jnr’s life, filled as it was with multiple aliases, wife and child desertion, and criminal activity, had a profound impact on his descendants. His ability to deceive authorities and his multiple marriages speaks to both his cunning and the limitations of investigative methods of the time. Exploiting the lack of coordinated recordkeeping and the difficulties in communicating across government departments and jurisdictions, Richard Jnr was able to fabricate new identities and evade the consequences of his actions. This deception was facilitated by the relative ease with which new identities could be assumed. Even though accurate records may have been kept, there was no efficient system to cross-check information across vast distances or between Australia's separate colonies. The isolated nature of towns, combined with fragmented jurisdictions and differing systems, made it difficult to track individuals consistently.

William Carpenter: Eight escapes from Victoria’s asylums

While Richard Snr and Maria’s eldest son Richard Jnr led a life of multiple marriages and many children, his siblings William and Elizabeth spent much of their lives in and out of Victoria’s asylums.

William Carpenter, the second son of Richard Snr and Maria, was born on 2 June 1844[79] in Devon, England. He arrived in Australia with his parents at the age of five in 1849. For the next two decades, little is recorded about him until a critical turning point in 1869.

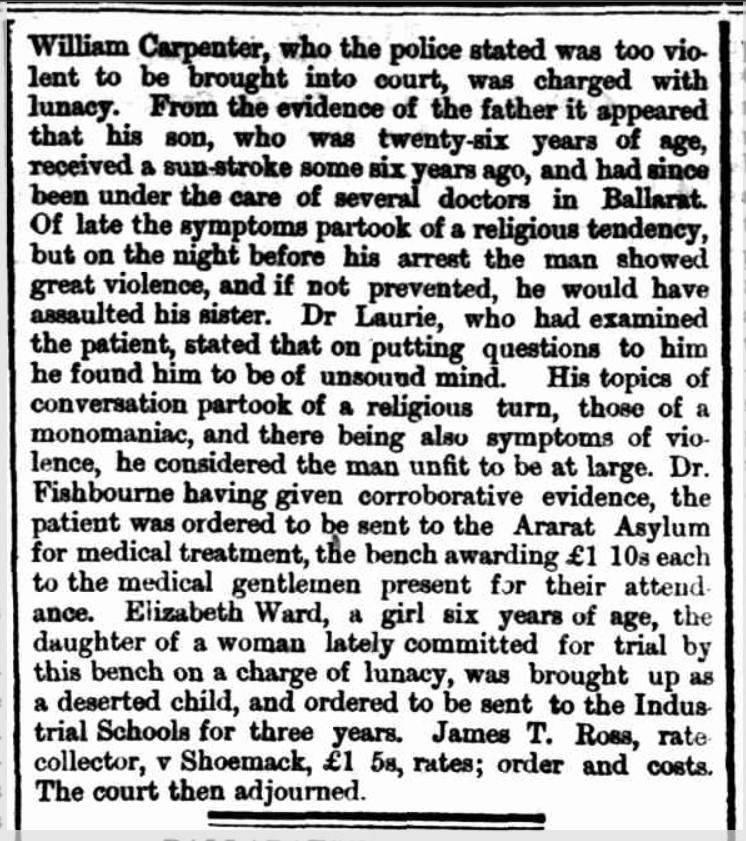

On 16 August 1869, at the age of 25, William was charged with lunacy before a local court. His father reported that William had suffered sunstroke six years earlier, leading to ongoing treatment by several doctors at Ballarat. His condition had recently worsened, manifesting in religious delusions and violent behaviour. The night before his arrest, he had threatened his sister. Doctors diagnosed him as of unsound mind. He was deemed unfit to be at large and was committed to the Ararat Asylum (Figure 10).[80]

Figure 10: William’s arrest, as reported in Ballarat Star, 17 August 1869, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112891585>.

William’s commitment followed the passage of the Lunacy Statute 1867 (Vic), which outlined the laws for the detention and treatment of people determined to be lunatics.[81] Admitted to the Ararat Asylum on 18 August 1869, he was discharged four and a half months later on 30 December 1869.[82] However, his freedom was brief. On 7 September 1870, he was arrested again and taken to the Learmonth Police Station; he ‘appeared to be in a dying state when brought to the lock-up’.[83] This second attack, occurring about six months after his first, was again attributed to sunstroke. Described as sober and industrious, William was diagnosed with melancholia and readmitted to the Ararat Asylum (Figure 11) on 10 September 1870.[84]

Figure 11: Inside the Ararat Asylum. PROV, VPRS 10516/P1 Register of Assisted Immigrants from the United Kingdom, Ararat Mental Hospital, Image 7.

Over the next decade, William repeatedly escaped from various asylums, only to be captured and returned: a pattern emerged—escape and return, interspersed with periods of trial leave and readmissions. His first escape from the Ararat Asylum occurred on 2 November 1871 while working outside with an attendant. He was recaptured and returned on 6 November.[85] On this occassion he remained at the asylum for two years and four months. He was released for one month’s trial leave on 14 May 1874 and returned on 4 July 1874. He was again granted a month’s leave on 14 October 1874 but returned early on 8 November 1874.[86]

William’s second escape from Ararat Asylum was during Christmas 1875, when he escaped on 22 December and was recaptured on 26 December. He was granted further trial leave on 1 June 1876 and returned on 22 August 1876.[87] On 28 January 1877, William made his third escape from Ararat Asylum. He was recaptured by 31 January and was granted a further period of leave on the same day.[88]

In May 1877, William was transferred to Kew Asylum, where records again described him as sober and industrious, with sunstroke cited as the cause of his condition. He escaped from Kew Asylum on 29 June 1877, marking his fourth escape from asylums. He remained at large for nearly a month before being recaptured on 27 July.[89]

During his time in asylums, financial contributions for his care were sought from his father, Richard Snr Carpenter, whose impoverished circumstances were highlighted by the Ballarat Shire Council in October 1877.[90] After spending three months at Kew Asylum, William was transferred to the new lunatic asylum at Ballarat in October 1877,[91] where he experienced episodes of epistaxis, diarrhoea and maniacal excitement.[92] Despite this, he continued escaping—on 2 February 1878, 8 July 1878 and 8 August 1878 (Figure 12)—and was recaptured quickly each time.[93] William was transferred back to Ararat Asylum on 28 August 1878, before his eighth and final escape on 30 October 1878. Recaptured three days later, he was granted open-ended leave on 14 November 1878, marking the beginning of a pattern of extended leave with voluntary readmissions.[94]

William’s repeated diagnoses, particularly melancholia, reflected the common medical practices of the time that categorised individuals based on a limited understanding of mental health. In these diagnoses, societal expectations and gendered norms played a significant role in shaping the conclusions reached by medical staff. As Coleborne notes, while diagnoses like mania and melancholia were common for both men and women in the nineteenth century, the interpretation of symptoms was often influenced by social perceptions of gender, with men more likely than women to be diagnosed with conditions such as general paralysis of the insane.[95] The documentation of William’s violent behaviour, religious delusions and threats towards family members was likely framed within colonial understandings of masculinity, which often linked emotional instability in men to external forces, such as sunstroke.

Figure 12: One of William Carpenter’s eight escapes listed in patient case books. PROV, VPRS 7405/P1 Case Books of Male Patients, Folio Numbers 1–157 Ballarat Asylum, p. 7.

After spending eight of the past 13 years in asylums, William was discharged as cured on 7 August 1882.[96] Post-discharge, he secured employment as a labourer, eventually purchasing land and building a modest, two-roomed hut, and accumulating significant savings.[97] His hut at Flint Hill was strikingly situated with a view of the Ararat Asylum, a constant reminder of his past. In August 1922, shortly after being discharged from the Ararat Hospital, William was found deceased in an outhouse at his home.[98] The cause of death was recorded as senile decay. He was buried at Ararat Cemetery a few days later.[99]

Elizabeth Carpenter: 60 years in the Ararat Asylum

William’s sister, Elizabeth, was also admitted to the Ararat Asylum (Figure 13). Born on 19 August 1858 at Burrumbeet, Elizabeth was the youngest daughter of Richard Snr and Maria.[100] Though her early years are largely undocumented, she, like her brother William, became entangled in the mental health system.

Figure 13: Elizabeth Carpenter’s photograph in the Ararat Asylum records. PROV, VPRS 7401/P1 Case Books of Female Patients, C, p. 133.

Elizabeth’s initial symptoms were noted by Constable Doyle, who documented her first attack in January 1879 (Figure 14). It had persisted for five months and was characterised by delusions, with medical practitioners confirming her condition (Figure 15). Her father described her erratic behaviour, violence towards her mother and restlessness. A near-drowning incident six years earlier was believed to have contributed to her condition.[101] Richard Snr stated:

I am living by keeping after cows—at Burrumbeet—my daughter Elizabeth will be 21 years of age next August. She has been eccentric in her manner for the last two months.

We first observed that when she went to bed she fidgeted about and patted the bed clothes and became very restless—she grew gradually worse and more sleepless—she began to destroy things in a meaningless way—and kept running away so that we had great difficulty in keeping her at home.

She does not seem to pay any attention to what is said to her and if she is chastised she seems more spiteful and determined to have her own way—she several times struck her mother, and once attacked her and marked her face all over. She once or twice threatened to kill her mother and to beat her.

One of her brothers has been in a Lunatic Asylum and is now out on probation. She fell into a waterhole and was nearly drowned about six years ago and I fancy the shock slightly unsettled her reason.

I do not think she has been quite the same since she had an attack of nervousness about two years ago but soon got over it.[102]

Figure 14: Police report, dated 27 January 1879, describing Elizabeth as ‘quiet, but noisy’. Ararat warrant file no. 1169 Elizabeth Carpenter, obtained under Freedom of Information, Department of Health, Victoria.

Figure 15: The order to detain Elizabeth and have her admitted to the Ararat Asylum was issued on 28 January 1879. Ararat warrant file no. 1169 Elizabeth Carpenter, obtained under Freedom of Information, Department of Health, Victoria.

R. Denham Pinnock diagnosed Elizabeth with incipient insanity, citing her lack of self-control and nervousness. Following this assessment, two justices of the peace agreed to her admission to the Ararat Asylum.[103] At the time of her admission on 28 January 1879, she was described as a 20-year-old dressmaker from Burrumbeet and as suffering from ‘mania’, with her current attack recorded as lasting two months. Her primary symptoms including being ‘excited and noisy’.[104]

Elizabeth’s persistent diagnoses of mania reflect broader societal attitudes towards gender and mental illness. As Coleborne highlights, more than a quarter of patients at Yarra Bend Asylum were diagnosed with mania, a trend that reflected not only the medical limitations of the time but also prevailing gender norms, which linked emotional distress in women to social instability.[105] Elizabeth’s restlessness—‘excited and noisy’—was likely seen as a deviation from the expected behaviour of women, particularly as her symptoms also disrupted familial and social harmony. Further, as Coleborne notes, the context of familial connections and social roles in colonial society often influenced both the diagnoses and the treatment patients received in asylums.

Elizabeth spent over eight months in the asylum before being released on 4 October 1879.[106] Her mother Maria passed away in February 1880.[107] On 17 August 1882, Elizabeth was readmitted to the Ararat Asylum after threatening to kill her father. Her case was reported in the Ballarat Star and Ballarat Courier, both papers detailing the circumstances of her arrest and the subsequent medical examinations that confirmed her insanity (Figure 16).[108]

Figure 16: Elizabeth’s case as reported in the Ballarat Courier on 18 August 1882.

During her second admission, Elizabeth was again diagnosed with mania. She remained in the asylum for over three years, not being released until December 1885.[109] Unfortunately, her freedom was short-lived. On 7 April 1886, Sergeant John Crowley arrested her, leading to her third admission to the Ararat Asylum.[110] Then 27 years old, her occupation was described as breaking in young cattle to milk and dressmaking. Sergeant Crowley noted her restlessness and tendency to wander, leading to her arrest at the Weatherboard Hotel:[111]

I arrested the patient Elizabeth Carpenter on warrant at the Weatherboard Hotel at Weatherboard near Learmonth. Her parents reside at Burrumbeet. She will not stop at home but wanders around without any apparent motive but restlessness. She was taken in out of charity by the landlady of the Weatherboard Hotel who knew her peculiarities. She has been in a lunatic asylum before.[112]

Upon examination by Dr Thomas Furneaux Jordan and Dr William Philip Whitcombe, Elizabeth was once again deemed a lunatic.[113] Readmitted to the Ararat Asylum, she would remain there for the rest of her life, with occasional brief periods of trial leave. Throughout her time at the asylum, Elizabeth found solace in the sewing room, though her behaviour varied from excited and noisy to threatening and violent. In her later years, she became deaf and seldom spoke.[114]

Elizabeth passed away at 9.25 am on 30 December 1947, aged 89. Her parents and siblings had all predeceased her. She spent more than 60 years of her life in the Ararat Asylum. At her inquest, held at 2.30 pm on the day of her death, Acting Coroner Mark Henry Forsyth concluded that Elizabeth’s cause of death was a cerebral embolism and cardiovascular degeneration. His report noted the absence of any living relatives (Figure 17). Elizabeth was buried in Ararat Cemetery the following day.[115]

Figure 17: Elizabeth Carpenter’s inquest notes the lack of any relatives at the time of her death. PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, 1947/1664.

Final thoughts

This article has examined the lives of the Carpenter family through the lens of public records, revealing the personal struggles and societal challenges they faced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From migration and crime to mental illness and institutionalisation, their experiences reflect the broader historical realities of colonial Victoria.

The institutionalisation of Elizabeth and William Carpenter cast a long and stigmatising shadow over the family, illustrating not only the deep personal toll of mental illness but also the limited understanding and support available at the time. Their stories highlight how colonial society often responded to mental health crises with confinement rather than care, leaving individuals and families to navigate a system that offered little hope of recovery.

Richard Jnr’s life, marked by deception, fraud and the fathering of at least 27 children, offered a different yet equally revealing perspective on survival in the face of hardship. His ability to repeatedly reinvent himself—abandoning families and assuming new identities—underscores the precarious nature of life on the margins of society. His ability to create new families, and the perceived lack of social responsibility, raises important questions about his own state of mind during a time of rapid change in Australia when many people faced economic and social hardship.

While this article has focused on Richard Jnr, William and Elizabeth, the lives of their siblings—Ellen, Emily, Henry and Edward—were also shaped by the challenges of their time. As they raised families of their own, contributing 24 children to the next generation, they too had to navigate the shifting social and economic landscapes of colonial and post-Federation Australia.

When Richard Snr and Maria Carpenter set sail for Australia in 1849, they could not have foreseen the extraordinary and, at times, tragic paths their children’s lives would take. Nor could they have imagined that, 175 years later, the records of their family’s interactions with government institutions would allow their descendants to reconstruct their long-forgotten stories. This article is a testament to the power of archival research—not just in uncovering hidden histories, but in connecting past and present, revealing a family’s journey across generations and reminding us that, even in official documents, deeply human stories endure.

Endnotes

[1] ‘Emigration to Australia’, Western Times (Exeter), 3 February 1849, p. 7.

[2] ‘Crediton’, Western Times (Exeter), 17 March 1849, p. 7.

[3] Devon Heritage Centre, 70A/PO/7759, 7759-7765; Devon Heritage Centre, 70A/PO/7820-7822.

[4] General Register Office, United Kingdom (GRO-UK), Richard Carpenter and Maria Dally, 21 October 1839, marriage registration, GRO reference: December 1839, St Thomas, Devonshire, UK, vol. 10, p. 369.

[5] GRO-UK, Susanna Rich, 23 December 1841, death registration, GRO reference: March 1842, Newton Abbot, Devonshire, UK, vol. 10, p. 111.

[6] GRO-UK, William Carpenter, 10 November 1841, death registration, GRO reference: December 1841, Williton, Somerset, UK, vol. 10, p. 351.

[7] GRO-UK, John Dally, 3 May 1848, death registration, GRO reference: June 1848, St Thomas, Devonshire, UK, vol. 10, p. 172.

[8] PROV, VPRS 14/P0 Register of Assisted Immigrants from the United Kingdom, Book No. 4A, pp. 142–143.

[9] PROV, VPRS 14/P0 Register of Assisted Immigrants from the United Kingdom, Book No. 5A, p. 39.

[10] Ibid., p. 48.

[11] Ibid., p. 49.

[12] Births, Deaths and Marriages, Victoria (BDM-V), Emily Carpenter, death registration no. 6879, 1933.

[13] BDM-V, Henry Carpenter, death registration no. 4614, 1862.

[14] BDM-V, Edward Carpenter, birth registration no. 5739, 1857.

[15] BDM-V, Elizabeth Carpenter, birth registration no. 16944, 1858.

[16] PROV, VPRS 13004/P1, Rate Book for 1864–1868, pp. 14, 36, 106, 118, 175; Rate Book for 1869–1876, pp. 14, 43, 81, 108, 133, 158, 181, 203; Rate Book for 1876–1884, p. 17.

[17] BDM-V, Henry Carpenter, death registration no. 4614, 1862.

[18] ‘Notice’, Star (Ballarat), 25 November 1861, p. 3, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66343720>.

[19] GRO-UK, Richard Carpenter, 5 January 1842, birth registration, GRO reference: March 1842, St Thomas, Devonshire, UK, vol. 10, p. 251.

[20] BDM-V, Richard Carpenter and Susan Downes, marriage registration no. 3415, 1865. There is some evidence to suggest that Susan went to New Zealand and spent her life there, but it is not conclusive. For the sake of brevity, I have refrained from including full details of what happened to all of Richard’s wives.

[21] Victoria Police Gazette, no. 42, 19 October 1865, p. 383.

[22] Births Deaths and Marriages, Queensland (BDM-Q), George Carpenter and Elizabeth Neylan, marriage registration no. 000530, p. 2304, 1867.

[23] BDM-Q, John Carpenter, birth registration no. 002657, p. 2304, 1868.

[24] Births Deaths and Marriages, New South Wales, Richard Joseph Carpenter, birth registration no. 5771, 1869.

[25] BDM-V, Thomas Carpenter, birth registration no. 14664, 1871.

[26] BDM-V, Mary Elizabeth Carpenter, birth registration no. 12944, 1873.

[27] BDM-V, Martin Carpenter, birth registration no. 3065, 1875

[28] BDM-Q, John Carpenter, death registration no. 001077, p. 2304, 1868.

[29] Victoria Police Gazette, no. 3, 17 January 1877, p. 17.

[30] Victoria Police Gazette, no. 38, 24 September 1879, p. 240.

[31] ‘Echuca Police Court’, Riverine Herald (Echuca), 27 August 1879, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113573051>; PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 8915 – 12311; Boys neglected – Register 12; and 8500 – 12310; Girls neglected, Book 9; Find & Connect, The Neglected and Criminal Children’s Act 1864, Victoria, <https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/entity/the-neglected-and-criminal-childrens-act-1864-2/>.

[32] ‘Vagrancy’, Nathalia Herald (Nathalia), 3 November 1893, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article280612595>; PROV, VPRS 516/P0, 6416–6913 (1896–1904), prisoner no. 6481; PROV, VPRS 8487/P0001, 23 September 1896 to 13 October 1898.

[33] ‘A peculiar case’, Shepparton Advertiser (Shepparton), 1 February 1901, p. 3, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article269951971>; PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, 1901/177.

[34] BDM-V, William Ross and Catherine Sutton, marriage registration no. 454, 1881.

[35] BDM-V, Charles Ross, birth registration no. 23850, 1881.

[36] BDM-V, Edward Carpenter, birth registration no. 3073, 1884.

[37] BDM-V, Emily Annie Carpenter, birth registration no. 28846, 1885.

[38] BDM-V, Kate Elizabeth Carpenter, birth registration no. 23777, 1887.

[39] BDM-V, Matilda Lavinia Carpenter, birth registration no. 3054, 1890.

[40] BDM-V, Ethel Dora Carpenter, birth registration no. 22431, 1891.

[41] BDM-V, Rebecca Ruth Carpenter, birth registration no. 31214, 1893.

[42] BDM-V, Lily May Carpenter, birth registration no. 27508, 1896.

[43] PROV, VPRS 1689/P0, Court of Petty Sessions Register (11.07.1890 – 31.01.1896), pp. 64, 65, 84, 86, 90, 91, 100, 107, 110, 126, 127; Court of Petty Sessions Register (31.01.1896 – 28.09.1904), pp. 12, 31.

[44] PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 23240 – 23540, pp. 170–173. Catherine eventually remarried in 1911 and went on to have three children. BDM-V, Frederick Cook and Catherine Sutton, marriage registration no. 2859, 1911; Frederina Rose Cook, birth registration no. 7506, 1902; Frederick Adolphus Sutton Cook, birth registration no. 25418, 1904; Adeline Frances Cook, birth registration no. 4546, 1907.

[45] PROV, VPRS 1689/P0, Court of Petty Sessions Register (31.01.1896 – 28.09.1904), pp, 51–53.

[46] BDM-V, Robert Sutton and Anna Elizabeth Sorenson, marriage registration no. 5663, 1898.

[47] BDM-V, Jane Lavinia Sutton, birth registration no. 24513, 1899.

[48] BDM-V, Mary Rebecca Sutton, birth registration no. 22195, 1901.

[49] BDM-V, Jane Lavinia Sutton, death registration no. 708, 1901.

[50] BDM-V, Elizabeth Anna Sutton, death registration no. 13981, 1901.

[51] Victoria Police Gazette, no. 7, 13 February 1902, p. 67.

[52] BDM-V, Robert Sutton and Mary Ann Moore, marriage registration no. 2205, 1902.

[53] BDM-V, Thomas Moore, birth registration no. 1377, 1901.

[54] BDM-V, Maggie Carpenter, birth registration no. 12481, 1903.

[55] BDM-V, Annie Moore, birth registration no. 15371, 1904.

[56] BDM-V, Robert Carpenter, birth registration no. 13825, 1906.

[57] BDM-V, Ellen Mary Somerton, death registration no. 06890, 1982.

[58] BDM-V, Cissy Jane, birth registration no. 18781, 1909.

[59] BDM-V, Elizabeth Carpenter, birth registration no. 20757, 1910.

[60] BDM-V, Mary Annie Carpenter, birth registration no. 443, 1912.

[61] BDM-V, Ivy Carpenter, birth registration no. 381, 1913.

[62] BDM-V, Richard Martin Carpenter, birth registration no. 9405, 1914.

[63] BDM-V, Hughie Joseph Carpenter, birth registration no. 450, 1918.

[64] BDM-V, Maria Carpenter, birth registration no. 18285, 1921.

[65] [No title], Ballarat Star, 3 March 1902, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207621352>.

[66] PROV, VPRS 2391/P0, Court of Petty Sessions Register (1901–03), p. 146; Kyneton, Argus, 14 July 1902, p. 6, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article9060067>.

[67] PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 34622 – 34920, pp. 185–189; ‘Neglected children’, Ballarat Star, 24 January 1911, p. 1, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article216623286>; ‘Neglected children’, Ballarat Star, 28 January 1911, p. 1, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article216623847>.

[68] BDM-V, Elizabeth Carpenter, death registration no. 273, 1911.

[69] PROV, VPRS 289/P0, Court of Petty Sessions Register (SET 2, 1911), p. 92.

[70] BDM-V, Mary Ann Carpenter, death registration no. 8343, 1912.

[71] BDM-V, Ivy Carpenter, death registration no. 249, 1913.

[72] PROV, VPRS 4527/P0 Ward Register, 34622 – 34920, pp. 185–189.

[73] BDM-V, William Carpenter, death registration no. 7509, 1922.

[74] ‘Father of 28 fined’, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 22 September 1925, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article45909389>; ‘A record family’, Horsham Times, 25 September 1925, p. 6, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article73008995>.

[75] BDM-V, Mary Ann Carpenter, death registration no. 15591, 1930.

[76] Private Carpenter Family Collection.

[77] BDM-V, Richard Carpenter, death registration no. 10906, 1932.

[78] PROV, VPRS 28/P3 Probate and Administration Files, 253/194.

[79] GRO-UK, William Carpenter, 2 June 1844, birth registration, GRO reference: June 1844, St Thomas, Devonshire, UK, vol. 10, p. 239.

[80] ‘Police’, Ballarat Star, 17 August 1869, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112891585>.

[81] Lunacy State 1867, <https://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/ls1867169/>.

[82] PROV, VPRS 7446/P1 Alphabetical Lists of Patients in Asylums, Ararat Asylum.

[83] ‘Learmonth’, Ballarat Star, 27 September 1870, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article218798781>.

[84] PROV, VPRS 7456/P1 Admission Warrants, Male and Female Patients, box 11.

[85] PROV, VPRS 7403/P1 Case Books of Male Patients, Vol. B.

[86] PROV, VPRS 7446/P1 Alphabetical Lists of Patients in Asylums, Ararat Asylum.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Ibid.

[89] PROV, VPRS 7398/P1, Case Books of Male Patients 1876, p. 151; PROV, VPRS 7456/P1 Admission Warrants, Male and Female Patients, box 11; PROV, VPRS 7681/P1 Discharge Registers, volume 1 (13/10/1872 - 21/05/1878), pp. 149, 161.

[90] ‘Ballaratshire Council’, Ballarat Courier, 2 October 1877, p. 4, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article211537248>.

[91] PROV, VPRS 7398/P1, Case Books of Male Patients 1876, p. 151; PROV, VPRS 7681/P1 Discharge Registers, vol. 1 (13/10/1872 – 21/05/1878), p. 161; PROV, VPRS 7405/P1 Case Books of Male Patients, Folio Numbers 1–157 Ballarat Asylum, p. 7; ‘The Government Gazette’, Australasian, 4 August 1877, p. 21, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article143268861>.

[92] PROV, VPRS 8257/P1 Medical Journals, 20 October 1877 – 6 September 1884, pp. 1, 3.

[93] PROV, VPRS 7446/P1 Alphabetical Lists of Patients in Asylums, Ararat Asylum.

[94] Ibid.

[95] C Coleborne, Insanity, identity and empire: immigrants and institutional confinement in Australia and New Zealand, 1873–1910, Manchester University Press, 2015, pp. 104–105, 116, 118–119.

[96] PROV, VPRS 7403/P1 Case Books of Male Patients, Vol. B.

[97] PROV, VPRS 28/P3 Probate and Administration Files, 184/750.

[98] [No title], Ararat Advertiser, 15 August 1922, p. 6.

[99] BDM-V, William Carpenter, death registration no. 7509, 1922.

[100] BDM-V, Elizabeth Carpenter, birth registration no. 16944, 1858.

[101] Ararat warrant file no. 1169 Elizabeth Carpenter, obtained under Freedom of Information, Department of Health, Victoria.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Ibid.

[104] PROV, VPRS 7401/P1 Case Books of Female Patients, B, p. 163.

[105] Coleborne, Insanity, identity and empire, pp. 104–105, 116, 118–119.

[106] PROV, VPRS 7446/P1 Alphabetical Lists of Patients in Asylums, Ararat Asylum.

[107] BDM-V, Maria Carpenter, death registration no. 127, 1880.

[108] PROV, VPRS 7401/P1 Case Books of Female Patients, C, p. 11; ‘News and Notes’, Ballarat Star, 17 August 1882, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202126744>; ‘News and Notes’, Ballarat Star, 18 August 1882, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202126811>; [No title], Ballarat Courier, 18 August 1882, p. 2, <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article250063859>.

[109] PROV, VPRS 7401/P1 Case Books of Female Patients, C, p. 11.

[110] Ibid., p. 133.

[111] Ararat warrant file no. 1820 Elizabeth Carpenter, obtained under Freedom of Information, Department of Health, Victoria.

[112] Ibid.

[113] Ibid.

[114] PROV, VPRS 7401/P1 Case Books of Female Patients, C, p. 133, and Continuation Notes on Admissions from Earlier Volume, p. 62; Ararat Case Book, obtained under Freedom of Information, Department of Health, Victoria.

[115] PROV, VPRS 24/P0 Inquest Deposition Files, 1947/1664; BDM-V, Elizabeth Carpenter, death registration no. 21850, 1947.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples